Most of us don’t think twice when we sign in to an app or approve a transaction. But for companies, getting that moment right is a constant challenge. Too many steps, and users drop off. Too few, and the system becomes vulnerable. That gap between convenience and security is exactly where US8677116B1 sits.

The patent describes a way to verify users with the help of a reusable, short-lived identifier sent between a device, a server, and the system the user is trying to access. It’s a practical idea to speed up authentication without compromising safety.

No wonder this patent is central to multiple lawsuits involving airlines, retailers, restaurant chains, and other large businesses .

To understand where this patent stands in the evolution of this tech, we used the Global Patent Search tool to trace earlier inventions, and how they contributed to this idea.

Understanding Patent US8677116B1

At the heart of US8677116B1 is a straightforward idea: give users a smoother way to prove who they are without weakening security.

The patent describes a setup where three things talk to each other i.e. the system you’re trying to access, your device, and a verification server in the middle.

Here’s what actually happens. When you try to access something secure, the system sends out a reusable identifier. It’s not a password or a one-time code. It’s a short-lived token that represents the action you’re trying to perform. Your device then sends back a copy of that identifier along with whatever verification information is needed. The server checks both signals, confirms they match, and decides whether you should be allowed in.

The idea is simple: a faster, more coordinated way to authenticate across laptops, phones, apps, and even physical systems. Instead of generating new codes every time, the patent proposes a controlled identifier that works for a brief period and keeps the process moving without compromising safety.

Key Features of US8677116B1

These are the main elements of US8677116B1:

1. A reusable identifier: Instead of generating a new code for every action, the system creates a short-lived identifier that represents what the user is trying to access. It lasts only for a limited period but removes the need for constant OTPs.

2. Two signals working together: The secured system sends the first signal. The user’s device sends the second. Both include the same identifier, and the second adds the user’s verification information. The server compares these and checks if everything matches.

3. Cross device flexibility: A user can trigger an action on one device and confirm it on another. This makes the method adaptable for laptops, phones, apps, and even physical systems.

4. Final authorization: If the server is satisfied with the verification, it sends an approval signal back to either the device or the system, allowing the user to continue.

All of this comes together to offer a smoother way for systems to confirm a user’s identity without slowing the experience.

A similar idea shows up in our Secure Matrix analysis of US7552870B2, where distributed authentication and cryptographic trust protect identity in large credit-based networks. It complements the layered flow described in US8677116B1.

Exploring The Technology Landscape of US8677116B1

US8677116B1 sits in a long line of authentication inventions. There are many patents that explored similar ways of sending signals, issuing temporary identifiers, and verifying a user across different devices.

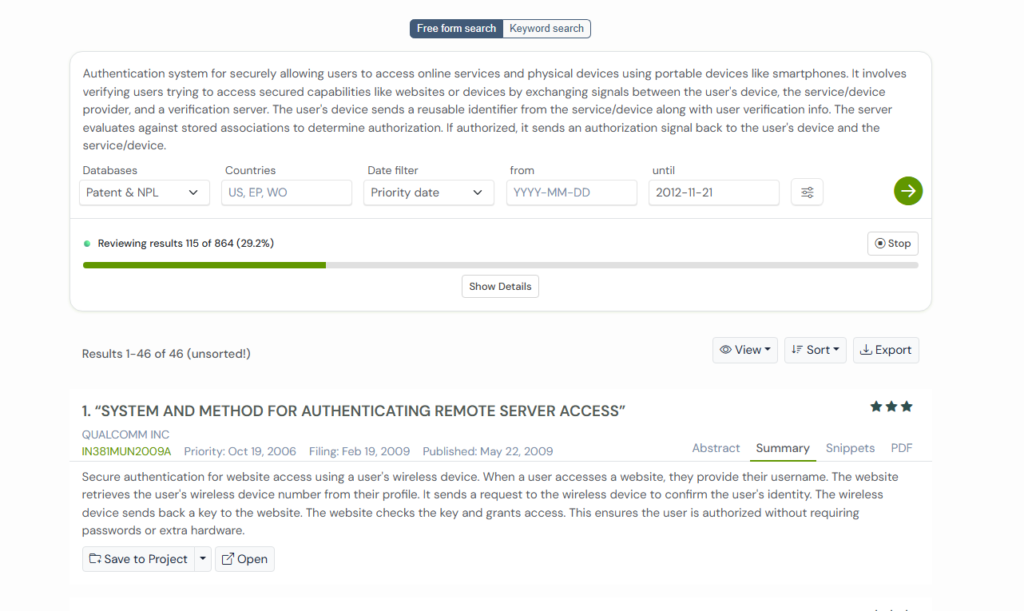

To see how this method fits into that larger story, we used the Global Patent Search(GPS) tool. GPS helped us trace older inventions that share the same structure or solve the same problem in slightly different ways.

Together, they show how the field gradually moved from simple passcodes to more flexible, coordinated authentication flows.

1. JP2003534589A

JP2003534589A was filed in 2001 by a team trying to fix a very real problem with early authentication systems. Back then, companies depended heavily on passwords, PINs, and hardware tokens.

Users forgot them, wrote them down, lost them, or chose ones that were too easy to guess. When millions of people needed access to secure online services, distributing physical tokens or encryption devices quickly became impractical.

This patent approached the issue differently by relying on a device almost every user already carried at that time, a mobile phone.

The method was simple. When a user attempted to access a secure service, the server generated a passcode and sent it directly to the user’s mobile device through a separate communication channel. The user then typed that passcode back into the system, and if it matched, access was granted.

What makes this important for US8677116B1 is how closely the structure aligns. Both patents rely on two separate signals, a temporary credential issued by the server, and both use a verification step where the system compares information sent by the service and the user.

The difference is that this older patent uses a one time passcode, while US8677116B1 moves toward a reusable, time limited identifier to streamline the same idea.

The Bigger Picture

The patent represents the transition from password-only systems to multi-channel authentication. It shows how early inventors tried to make security stronger without requiring users to carry specialized hardware or remember complex information.

By using a mobile device as the secondary channel, it paved the way for the authentication experiences we consider normal today.

You can see this layered approach reflected in US8098153B2 as well, where its emergency-monitoring framework mirrors the matrix-driven access control model behind US8677116B1.

2. US20030046541A1

US20030046541A1, was filed in 2002, by inventors trying to simplify how users authenticate across different services. At the time, people were dealing with multiple passwords, cards, and PINs for different systems, and service providers used completely different mechanisms to verify identity.

This patent proposed a universal approach where a user could request access to any service and the verification would be handled by a central authentication server.

The idea works like this. A user requests a service. The service provider forwards that request to an authentication server. The authentication server then contacts the user’s authentication device, waits for a confirmation, checks if the confirmation is valid and timely, and then tells the service provider whether the user should be allowed in. It turns the authentication server into a trusted middle point between the user and any service provider.

The overlap with US8677116B1 appears in the structure of the exchange. Both patents rely on two separate signals coming from two different places. Both depend on a server in the middle that checks whether the information matches before granting access. And both separate the device requesting the service from the device confirming the authentication, creating a coordinated verification flow.

The Bigger Picture

The patent shows an early push toward unified authentication, where one system could verify a user across many services. It set the stage for more flexible, multi-device authentication flows that later patents, including US8677116B1, build upon with faster and more streamlined methods.

A crossover example appears in US10796137B2, where identity is validated through ticket-linked codes and live facial matching. The structure closely mirrors the multi-device verification approach refined in US8677116B1.

3. US7233997B1

US7233997B1 was filed in 1998 by British Telecommunications PLC exploring how to make repeated web authentication faster and less resource-heavy. At the time, users had to enter a username and password every single time they requested a document from a protected website. If a page contained multiple images or files, the server had to authenticate the user again and again, creating an unnecessary load. This patent tried to solve that by introducing a mechanism where, after the first successful authentication, the system would issue an identifier and store it on the user’s device.

Once the identifier was stored, the user’s browser automatically sent it with every new request. The authentication server kept track of which identifiers belonged to currently authenticated users, and the application servers checked that list before serving any protected content. It essentially turned one long, repetitive login session into a smooth, continuous experience.

The overlap with US8677116B1 appears in how both patents use a server-issued identifier to control access. Both rely on a temporary credential that travels back from the user’s device and helps confirm whether the request should be allowed. And both reduce the need for repeated password checks by shifting trust to an identifier that the server can validate quickly.

The Bigger Picture

The patent reflects one of the early moves toward seamless session management and reduced authentication friction on the web. It shows the industry’s shift from repetitive password prompts to short-lived identifiers, a path that later authentication systems, including US8677116B1, continue with more flexible and cross-device methods.

This selective-encryption approach has its roots in earlier work like US7057960B1, where section-level refresh logic was designed to cut redundant power cycles. The same principle of controlled, efficient validation shows up in US8677116B1’s identifier-based flow.

4. US20020091945A1

US20020091945A1 was filed in 2001 by David Ross, who was trying to solve a growing security headache of that era. Passwords kept failing, identity theft was rising, and companies didn’t want to store huge amounts of personal data in one place. This patent introduced a clever middle path: instead of relying on one database or one token, it used small pieces of personal information held across multiple independent databases to verify whether a remote user was actually who they claimed to be.

The system works through a verification engine that sends predefined questions to the user, forwards their answers to the corresponding database operators for validation, and receives a confidence score back from each operator. Those individual scores are combined into one final confidence rating. The idea was simple but powerful: spread the risk, avoid centralization, and authenticate a user using information that only legitimate institutions would know.

The overlap with US8677116B1 shows up in how both patents rely on server-driven verification instead of single static secrets. One uses reusable identifiers and device-based confirmation, the other uses cross-database confidence checks, but both shift the burden away from passwords and towards server-managed, dynamic authentication paths that make impersonation much harder.

The Bigger Picture

The patent reflects an early attempt to balance privacy with security by avoiding centralized identity storage. It opened the door for distributed trust models, a philosophy echoed in modern authentication systems that combine device signals, server logic, and layered verification instead of relying on a single piece of user knowledge.

You can explore a concept that aligns closely with how US11736499B2 models execution-flow deviations to catch early signs of injection behavior.

5. US20020184496A1

US20020184496A1 was filed in 2001 by Christopher Mitchell and Wei-Quiang Guo, right when the internet was getting flooded with new users, including children. Websites suddenly had to manage parental consent under COPPA, and most of them struggled with the cost, complexity, and compliance burden. This patent introduced a system that let a parent manage a child’s access across multiple websites without forcing the child to log in everywhere or manually re-verify themselves.

The core idea was simple. A parent and child were linked through profiles on an authentication server. Whenever the parent updated consent settings, those changes could be securely shared with any affiliated website through a validation code. The child didn’t need to be logged in on every device for updates to take effect. Everything flowed through one trusted server that handled identity, consent, and communication.

US20020184496A1 overlaps with US8677116B1 in how both patents shift verification away from the user and into a server-driven authentication flow. One focuses on verifying device-based user actions using reusable identifiers, while this one focuses on transferring permissions and relationships across websites using validation codes. But the philosophy is the same: reduce friction for the user and centralize trust in a controlled system.

The Bigger Picture

The patent captures an early effort to make online safety and consent management seamless, especially for families. It paved the way for centralized identity profiles and cross-site permissions, ideas that later authentication systems expanded into single sign-on, delegated access, and unified account management.

Multi-factor identity in US8677116B1 also aligns closely with the vendor-issued token architecture in US7177838B1, showing how authentication and payment verification gradually converged into unified digital commerce flows.

Comparing the Patents That Shaped Modern Authentication

Before diving into the table, it helps to see how these older ideas shaped the authentication flow behind US8677116B1. Each of these patents approached security from a different angle. Some relied on mobile devices, some on centralized servers, some on distributed verification.

When viewed together using the Global Patent Search tool, they show how the industry slowly moved away from simple passwords and toward multi-signal, server-managed authentication.

The table below captures how each invention contributed to that journey and where it overlaps with the structure of US8677116B1.

| Patent Number | What the Patent Is About | Key Focus | Core Mechanism | Connection with US8677116B1 |

| JP2003534589A | Mobile-based two-channel authentication | Making authentication stronger without relying on passwords or hardware tokens | Server sends a passcode to the user’s mobile device. User types it back. The system compares both values and grants access if they match. | Both use two independent signals. Both compare what the server sends vs what the user returns. The difference is this patent uses a one-time code, while US8677116B1 uses a reusable, time-limited identifier. |

| US20030046541A1 | Universal authentication across many services | Unifying login for different service providers using one central system | A service provider forwards the user’s request to an authentication server. The server contacts the user’s authentication device, waits for confirmation, validates it, and then instructs the service provider to allow or deny access. | Both rely on a server in the middle checking two different signals. Both separate the device requesting the service from the device confirming authentication. |

| US7233997B1 | Simplifying repeated web authentication | Reducing repeated username/password checks for protected content | After first login, the system issues a stored identifier. The browser automatically returns it with every document request. Servers validate it against a list of active sessions. | Both use server-issued temporary identifiers to control access. Both reduce friction by replacing repeated password checks with quick identifier-based validation. |

| US20020091945A1 | Multi-database identity verification | Verifying identity without storing all personal data in one place | A verification engine sends predefined questions to the user, forwards responses to independent databases, gathers confidence scores, and combines them into a final authentication decision. | Both rely on server-driven verification instead of static passwords. Both strengthen security by validating multiple signals before granting access. |

| US20020184496A1 | Centralized parental consent and delegated access | Letting parents manage a child’s access across multiple websites | Parent–child profiles are linked on an authentication server. Consent changes are securely shared with any affiliated website using a validation code. | Both shift the decision-making to a trusted server. Both reduce user friction by handling verification or permissions behind the scenes using secure identifiers or validation tokens. |

The encryption-gate pattern here also ties neatly into US7203844B1, which uses recursive key-management protocols to keep authentication flexible and secure across changing device states.

Mapping the Bigger Picture with the Global Patent Search Tool

Authentication has evolved through countless small ideas, and each patent captures only a slice of that journey. It’s only when you look at how those inventions connect that the larger story starts to make sense.

That’s where the Global Patent Search tool becomes useful. It helps you trace how different authentication models matured over time, from early two-channel passcodes to reusable identifiers and server-driven verification. Instead of flipping between long documents, GPS brings the pieces together so you can see how one idea shaped the next.

Here’s how GPS simplifies that discovery:

- Start from any patent: Type in something like US8677116B1 or even describe it briefly. GPS immediately surfaces patents dealing with multi-step verification, session identifiers, or server-managed authentication.

- Spot meaningful overlaps: You’ll see short claim snippets that show how earlier systems handled passcodes, tokens, or identity signals, and how they echo the structure of the subject patent.

- Dig deeper when needed: Open full documents to explore design changes, security models, or how old ideas were adapted for newer technologies.

- Follow unexpected connections: GPS often reveals links across surprisingly different areas, from mobile authentication to parental consent systems. These patterns help you understand how authentication techniques moved across industries.

By turning individual patents into a connected view, GPS helps researchers and analysts see how the subject patent fits into a broader evolution. It’s a simple way to follow the path from concept to real-world implementation.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why do some systems use two signals instead of one?

Using two independent signals makes it harder for an attacker to impersonate the user. The server receives one signal from the secured system and one from the user’s device, and access is granted only when both match.

2. Is it secure if the identifier is reusable?

Reusable identifiers are time-limited and tied to both the secured system and the user’s device. Even if someone intercepts it, it becomes invalid quickly and cannot be used beyond its intended scope.

3. What happens if the user’s verification device is unavailable?

Many systems offer fallback options, such as backup codes or alternate verification methods. But access is usually restricted unless the system can confirm the user in a secure way.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice. The related patent references mentioned are preliminary results from the Global Patent Search (GPS) tool and do not guarantee legal significance. For a comprehensive related patent analysis, we recommend conducting a detailed search using GPS or consulting a patent attorney.