Most restaurants already follow a familiar rhythm. Customers sit down, review the menu, and place an order when a server is available. The process works, but its pace is shaped more by staff timing than by customer readiness.

Ordering can only begin when someone is free to take it, confirmation depends on how clearly the order is heard and remembered, and payment waits for yet another interaction. None of this feels broken, but each step adds quiet operational dependency.

As restaurants grew busier and staff became expensive and harder to find, that dependency started to matter.

US7831475B2 addresses this by shifting routine ordering tasks away from staff without turning the menu into a full computer. The patent now sits at the center of the ongoing dispute between OrderMagic LLC and MTY Food Group Inc.

To understand how this approach emerged and how earlier ordering systems influenced it, we used the Global Patent Search (GPS) tool to trace related inventions over time.

What US Patent US7831475B2 Is Really Solving

By the time US7831475B2 was filed, restaurants were already moving away from fully staff-driven ordering. Customers were used to browsing menus on their own, making decisions independently, and expecting faster turnaround once they were ready.

US7831475B2 doesn’t challenge that behavior. It builds around it.

Instead of digitizing the menu itself or forcing customers into a new interface, the system preserves the physical menu exactly as people know it. What changes is what happens underneath. Each menu item is paired with a corresponding input. When a customer presses it, the system quietly records that selection.

A small display provides immediate confirmation, so choices are visible and reversible. Page changes are detected automatically, allowing the same inputs to adapt as the customer moves through the menu. Nothing new needs to be learned. There are no screens to navigate and no instructions to follow.

Once the customer is done, the order is transmitted wirelessly to the kitchen or ordering system. Payment can happen through the same setup, without waiting for a check or a return visit from staff.

Key Features of US7831475B2:

At a basic level, this patent is about letting customers order and pay without waiting for someone else to step in.

- Customers select items directly from a physical menu using built-in inputs.

- Each selection is confirmed immediately on a small display.

- The system detects page changes so the same inputs work across the entire menu.

- Orders are transmitted wirelessly to the kitchen or ordering system.

- Payment can be completed from the same setup without waiting for staff.

- Customers can request assistance without interrupting the ordering flow.

Nothing here is flashy. The value is in removing waiting, repeating, and manual handoffs. The menu stays familiar, but the process behind it becomes faster and more predictable.

Long before touchscreens and mobile apps, infrared remote controls showed how simple, directional wireless signals could transmit user intent reliably. Patents such as US4377006A formalized this approach without relying on complex timing or software.

5 Earlier Patents That Shaped Remote Ordering Systems

The idea of letting customers place orders without staff involvement had been explored for years, through kiosks, early electronic menus, and basic remote ordering tools.

What changed over time was not the goal, but the execution. Earlier systems struggled with complexity, cost, and rigidity. Some relied on full computers. Others required constant supervision or manual setup.

To understand how those ideas evolved, we used the Global Patent Search tool to trace earlier patents that tackled pieces of the same problem.

Let’s explore some of them.

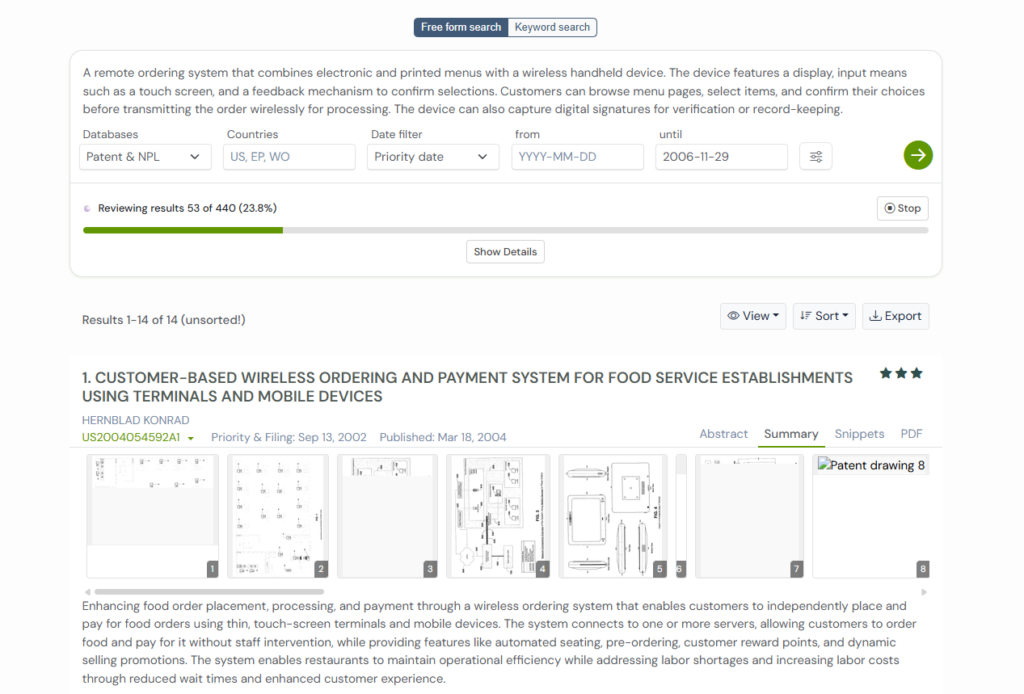

1. US2004054592A1 – Customer-Based Wireless Ordering and Payment System

US2004054592A1, filed in 2002, came from a time when restaurants were actively searching for ways to remove waiting from ordering and payment. The solution proposed here is direct and ambitious.

Customers place orders and make payments using thin touch-screen terminals or their own mobile devices. Orders are sent wirelessly to a central server, and payment is handled digitally using cards, mobile wallets, or prepaid systems. The system also supports pre-ordering, loyalty points, digital receipts, and real-time promotions pushed to customers.

In effect, this invention tries to move the entire restaurant flow onto networked devices. Menus, ordering, payment, and promotions all live inside software-driven terminals connected to servers.

Why This Approach Mattered

This patent showed that customer-driven ordering was technically possible without staff involvement. But it also revealed a limitation i.e., speed came at the cost of complexity. Touchscreens, batteries, servers, and software had to work flawlessly in environments filled with spills, heat, and constant use.

2. US2007239565A1 – Remote Ordering Device

US2007239565A1, filed in 2007 by Remote inc. looks at ordering from a very practical angle. It starts with situations where speaking to a server or leaning out to press a button is inconvenient or simply not possible, like drive-through lanes or busy service counters.

The patent introduces a handheld remote ordering device that lets customers select items, review quantities and prices, and send orders electronically to a central station. The order is shown on a small display so customers can correct mistakes before submitting the order. Payment can also be handled through the same device using cards or other electronic methods.

What makes this patent different is its flexibility. The device can be used by customers, by servers inside a restaurant, or even across other environments like retail stores, airports, or service facilities.

Why This Approach Mattered

This patent showed that removing verbal ordering improved accuracy and speed. It also highlighted a shift toward portable, user-controlled ordering, where the order travels digitally instead of physically.

Many early ordering and payment systems relied on short-range wireless links. Bluetooth, formalized through patents like US6590928B1, made reliable device-to-device communication practical inside restaurants, cars, and other crowded environments.

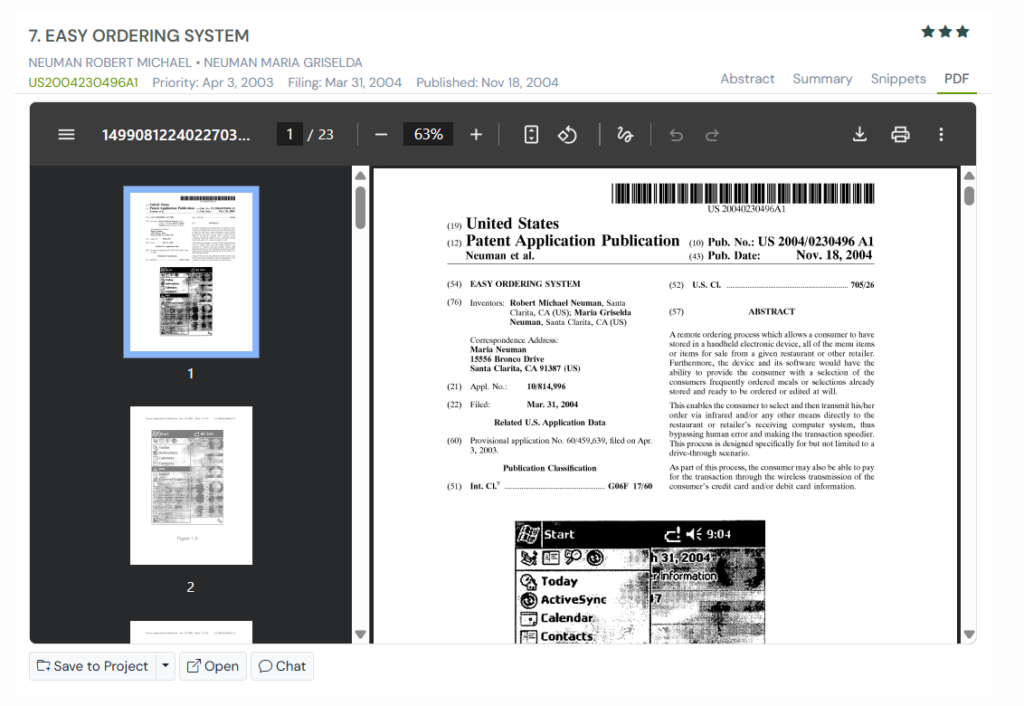

3. US2004230496A1 – Easy Ordering System

Filed in 2004, US2004230496A1 focuses on a problem most people recognize from drive-throughs and busy counters: talking through speakers, repeating orders, and still getting things wrong.

The system lets customers store full restaurant menus on a handheld device and build orders in advance. Instead of speaking to an order taker, the customer selects items on the device and wirelessly sends the order directly to the restaurant’s system. Prices, quantities, and confirmations appear on the screen before the order is sent, reducing mistakes and delays.

A key part of this invention is pre-saved orders. Regular customers can save common meals like breakfast, lunch, or family orders and reuse them with a single action. Payment information can also be transmitted wirelessly, further shortening the interaction.

The patent puts strong emphasis on accessibility. It is designed to help people who are deaf, mute, shy, non-native speakers, or simply uncomfortable with verbal ordering.

Why This Approach Mattered

This invention showed that ordering does not need conversation to work well. By separating selection from speech, it improved speed, accuracy, and inclusivity.

At the same time, it relied on personal handheld devices and stored digital menus, which added setup and device dependency that later systems aimed to reduce.

4. US2002138350A1 – System and Method for Placing Orders at a Restaurant

US2002138350A1, filed in 2002, tackles a familiar frustration with drive-through and walk-up ordering: remembering long orders, repeating them under pressure, and still getting something wrong.

The idea is simple. Customers store an entire restaurant menu on a handheld computer and build their order before they arrive. Selections can be saved, edited, and reused later. When the customer reaches the restaurant, the stored order is transmitted wirelessly to a receiving station near the drive-through lane or counter, where it is sent directly to the kitchen system.

Instead of reading items aloud or tapping through a public screen, the customer transfers a complete, pre-checked order file. This reduces ordering time and avoids mistakes caused by noise, stress, or miscommunication.

Voice assistants introduced a new way to interact with systems, but they also reintroduced ambiguity. Patents like US9130900B2 show how much effort is required to translate spoken language into reliable, actionable commands.

Why This Approach Mattered

This patent clearly separates decision-making from order placement. Customers choose items in advance, in a calm setting, and only transmit the final result at the restaurant. It highlighted the value of stored menus and reusable order files, especially for families, group orders, and repeat visits.

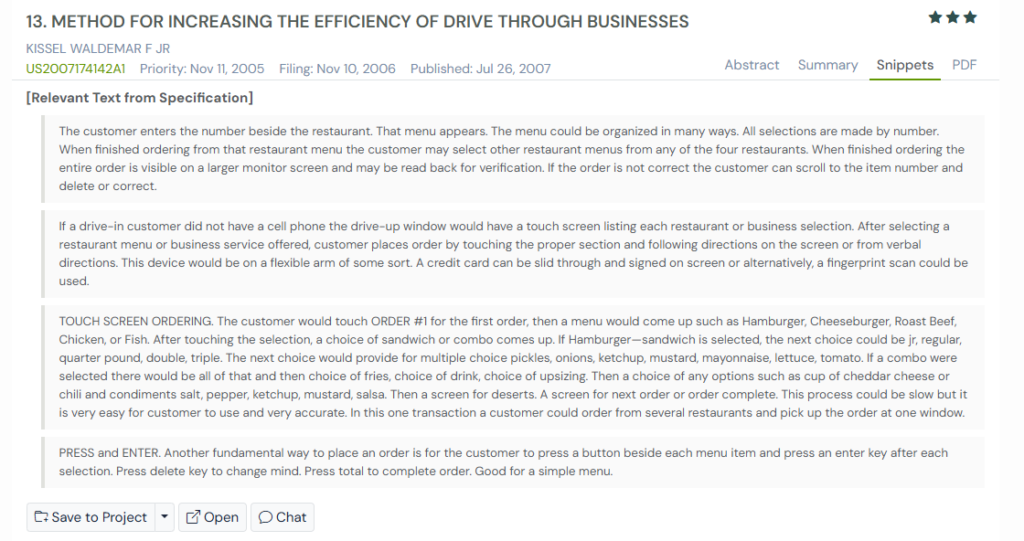

5. US2007174142A1 – Method for Increasing the Efficiency of Drive-Through Businesses

US2007174142A1, filed in 2006, looks at drive-through efficiency from a systems point of view rather than a device one.

The core idea is to replace verbal ordering with structured, step-by-step selection. Customers place orders by pressing numbers or touching on-screen options that guide them through the menu. Each choice leads to the next, from item type to size, add-ons, sides, drinks, and desserts. The full order is shown on a screen at the end so customers can review, edit, or delete items before confirming.

The system also allows a single customer to order from multiple restaurants or services in one transaction, then pick everything up at one window. The payment is handled directly at the ordering point using cards, signatures, or biometric input.

Why This Approach Mattered

This patent showed that accuracy in drive-through ordering could be improved by forcing structure into the process. By breaking ordering into predictable steps and eliminating spoken communication, it reduced misunderstandings and repeat corrections.

Comparison of Earlier Remote Ordering Patents

Each of these patents approached ordering efficiency from a different angle. This comparison highlights what each one tried to solve, what it did well, and how it connects to the approach taken in the subject patent US7831475B2.

| Patent Number | Core Idea | Ordering Method | Key Strength | Connection to Subject Patent (US7831475B2) |

| US2004054592A1 | Fully digital restaurant ordering and payment | Touch-screen terminals and mobile devices connected to servers | Complete digital flow including ordering, payment, and promotions | Demonstrates what happens when intelligence is pushed entirely into screens and software, which US7831475B2 deliberately avoids |

| US2007239565A1 | Portable, user-controlled ordering | Handheld remote device with display and inputs | Flexible ordering without verbal communication | Shows the value of portable ordering while highlighting the hardware burden later reduced by US7831475B2 |

| US2004230496A1 | Pre-saved digital menus and orders | Handheld device storing menus and transmitting orders | Speed, accuracy, and accessibility for repeat orders | Introduces pre-selection and reuse concepts later simplified in US7831475B2 |

| US2002138350A1 | Advance menu selection before arrival | Handheld computer with menu application | Separates decision-making from order transmission | Influences the idea of separating choice from submission, which US7831475B2 achieves without full menu storage |

| US2007174142A1 | Structured, step-by-step ordering | Touch screens or numbered input stations | High accuracy through guided selection | Highlights the trade-off between structure and speed that US7831475B2 balances differently |

How Global Patent Search Helps Connect These Ordering Ideas

When you look at restaurant ordering patents one by one, each invention feels like a small fix to a specific problem. One focuses on touch screens. Another on handheld devices. The third on structured menus. The real insight comes when you step back and see how these ideas evolved over time.

That’s where the Global Patent Search tool becomes useful.

Instead of looking at patents in isolation, GPS helps you trace how concepts like non-verbal ordering, pre-selection, structured input, and digital transmission slowly converged into more efficient systems.

How to Use GPS for This Analysis:

- Start with the subject patent: Enter the patent number to surface related inventions.

- Sort by relevance: Use the relevance sorting feature to bring forward patents that solve similar problems.

- Scan summaries first: Read short summaries or snippets to quickly understand what each patent is trying to fix before opening the full specification.

- Follow earlier filings: Move backward through cited and related patents to see how ideas like handheld ordering, structured menus, and digital transmission developed over time.

Want to explore how real-world ordering systems evolved without getting lost in dense patent language?

Try the Global Patent Search tool today and see the full picture behind modern restaurant technology.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why do drive-through orders often take longer than expected?

Drive-through delays usually come from verbal miscommunication, complex menu choices, and repeated corrections. Background noise, unclear speakers, and last-minute changes further slows the process. When orders are structured or pre-selected instead of spoken, these delays drop significantly.

2. How does digital ordering improve accuracy in restaurants?

Digital ordering removes guesswork. Customers see items, options, and prices clearly before confirming. This reduces mistakes caused by misheard requests, accents, or rushed conversations, leading to fewer remakes and smoother kitchen operations.

3. Is touch-screen ordering faster than speaking to an order taker?

For simple orders, touch-screen systems can be slightly slower. For complex or repeat orders, they are often faster overall because customers can review and confirm everything at once instead of correcting mistakes later.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice. The related patent references mentioned are preliminary results from the Global Patent Search tool and do not guarantee legal significance. For a comprehensive related patent analysis, we recommend conducting a detailed search using GPS or consulting a patent attorney.