Dr. Squatch, LLC v. The Procter & Gamble Company IPR2024-01174: Case Overview

Dr. Squatch, LLC v. The Procter & Gamble Company (IPR2024-01174) is a PTAB post-grant proceeding challenging U.S. Patent No. 11,497,706, owned by The Procter & Gamble Company.

The challenged patent relates to solid deodorant stick compositions, particularly aluminum-free formulations built around:

- structurants and wax systems that control hardness and wear,

- antimicrobial actives such as zinc oxide, magnesium hydroxide, and sodium bicarbonate,

- emollients and oils (e.g., sunflower oil, jojoba oil), and

- optional fragrance and essential-oil components.

Although positioned in the context of modern “natural” deodorants, the technical record shows that the asserted concepts draw from decades of cosmetic chemistry and formulation practice, spanning patents, textbooks, scientific literature, and publicly available product disclosures.

Distribution of References in the Official PTAB Record

The petitioner’s exhibit list reflects the breadth of sources relevant to deodorant formulation. As shown in the table below, the official record spans U.S. and non-U.S. patents, non-patent literature, cross-domain references, and procedural materials.

| Category | Count | Exhibits & Description |

| US Patents | 19 | **Patents: • Ex. 1025: US 5,585,092 • Ex. 1026: US 9,610,237 • Ex. 1041: US 4,049,792 • Ex. 1043: US 4,919,934 • Ex. 1045: US 10,966,915 • Ex. 1047: US 6,123,932 • Ex. 1053: US 10,905,647 • Ex. 1054: US 5,976,514 • Ex. 1055: US 5,429,816 • Ex. 1062: US RE38,141 • Ex. 1082: US 11,540,999 • Ex. 1083: US 5,019,375 Patent Applications:** • Ex. 1008: US 2007/0166254 (“Bianchi ’254”) • Ex. 1014: US 2005/0142085 • Ex. 1027: US 2014/0199252 • Ex. 1056: US 2019/0000734 (“Sturgis”) • Ex. 1057: US 2016/0089321 (“Anconi”) • Ex. 1060: US 2008/0287377 |

| Non-US Patents | 3 | • Ex. 1015 / 1049: WO 2012/098189 (English Translation) • Ex. 1072: EP 0471392 |

| NPL (Non-Patent Literature) | 36 | **Scientific Articles, Handbooks, & Technical Data: • Ex. 1005: Lamb (1946) • Ex. 1013: Laden et al. (1999) • Ex. 1019: White (2014) • Ex. 1021: Khuntayaporn & Suksiriworapong (2017) • Ex. 1022: Corral et al. (1988) • Ex. 1023: Emanoil (2006) • Ex. 1024: Shahtalebi et al. (2013) • Ex. 1028: Lambert (2011) • Ex. 1029: Pasquet et al. (2014) • Ex. 1030: Carvalho (2011) • Ex. 1031: Heisterberg et al. (2011) • Ex. 1032: Handley & Burrows (1994) • Ex. 1036: Schueller & Romanowski (2003) • Ex. 1037: Siquet & Devleeschouwer (2009) • Ex. 1039: Compendium of Food Additive Specifications (2005) • Ex. 1042: Dean (1999) • Ex. 1058: Stoia et al. (2015) • Ex. 1061: Sánchez et al. (2016) • Ex. 1063: Sandha et al. (2009) • Ex. 1064: Chen et al. (2014) • Ex. 1065: Material Safety Data Sheet, Jojoba Esters (2008) • Ex. 1066: Al-Rawi et al. (2018) • Ex. 1068: Navale et al. (2016) • Ex. 1069: IFSCC Monograph No. 6 (1998) • Ex. 1070: Abendrot et al. (2018) • Ex. 1071: Aniston (2015) • Ex. 1084: Cosmetic Science and Technology (2017)Web Publications & Marketing (Prior Art):** • Ex. 1007: Native Wayback Archives (2015-2016) • Ex. 1009, 1016, 1017, 1018: SoapDeliNews Archives (2012-2017) • Ex. 1020: The Crunchy Urbanite (2013) • Ex. 1010, 1011, 1012: News Articles (CNBC, Well+Good, S&P Global) |

| Cross-Domain References | 3 | • Ex. 1003: US 11,433,018 (“Lesniak”) • Ex. 1004: US 9,314,412 (“Phinney”) • Ex. 1006: US 6,048,518 (“Bianchi ’518”) |

| Legal / Procedural | 16 | Declarations: Ex. 1002 (Michniak-Kohn), 1059 (Pinto), 1086 (Michniak-Kohn Reply)Prosecution/File History: Ex. 1033, 1034, 1035, 1051, 1077 Litigation Documents: Ex. 1040 (Complaint), 1081 (Deposition Transcript)Evidence/Other: Ex. 1038 (Fed. Reg.), 1046 (C.F.R.), 1048 (CV), 1078 (Test Report), 1079 (Photos), 1080 (Marking Statement) |

| Reserved | 9 | Exhibits 1044, 1050, 1052, 1067, 1073, 1074, 1075, 1076, 1085 |

| TOTAL | 86 | Total Exhibits Listed (77 Active + 9 Reserved) |

The Technical Core of the Dispute

At the heart of IPR2024-01174 is whether the claimed deodorant compositions represent more than:

- known deodorant sticks (including antiperspirants),

- routine substitution of antimicrobial agents,

- predictable adjustment of wax levels to achieve target hardness, and

- selection of familiar emollients and oils.

The petitioner’s case relies heavily on Lesniak (U.S. 11,433,018), Phinney (U.S. 9,314,412), and Bianchi (U.S. 6,048,518 / 2007-0166254), arguing that these references collectively disclose:

- deodorant sticks without aluminum,

- zinc- and magnesium-based antimicrobials,

- hardness ranges measured using standard industry methods, and

- stable, consumer-acceptable stick formulations.

Supporting this are textbook-level disclosures—such as Antiperspirants and Deodorants (Laden, 1999) and IFSCC monographs—that frame deodorants as a mature, well-understood technical field.

Why Prior-Art Coverage Is Hard in Cosmetic Formulations

Unlike emerging software or AI fields, cosmetic science advances incrementally. It is also widely dispersed across patents, academic literature, textbooks, and public product disclosures. Because of this fragmentation, teams increasingly rely on semantic second-pass tools such as Global Patent Search (GPS) to test whether critical formulation disclosures fall outside conventional search boundaries.

The same technical concept—such as improving mildness while preserving foam or wear—may be described using:

- different ingredient names,

- alternate functional framing (e.g., “conditioning” versus “bar integrity”), or

- non-patent terminology common in cosmetic chemistry literature.

As a result, even thorough keyword- and classification-based searches can develop visibility gaps, particularly when:

- older patents predate modern branding language,

- relevant disclosures appear in non-U.S. filings, or

- ingredient functionality is described indirectly rather than claimed explicitly.

| What Is Global Patent Search (GPS)? Global Patent Search (GPS) is an AI-powered patent and literature search platform that enables semantic, natural-language exploration across global patent databases and non-patent literature.Rather than relying solely on keyword matching, GPS helps identify:technically similar disclosures described using different vocabulary,formulations discussed outside conventional patent classifications, andcross-domain references relevant to cosmetic science and materials chemistry. |

What a Semantic Second Pass Reveals

Using GPS, we conducted a second-pass prior-art review centered on the challenged P&G patent and compared the results against the official PTAB exhibit list.

The goal was not to re-litigate relevance, but to test coverage:

- Which references appear in both the official record and GPS results?

- Which appear in only one source?

- What new insights can this search surface?”

To structure the analysis, references were grouped as:

- Common – appearing in both the PTAB exhibit list and GPS results

- Uncommon – appearing in one source but not the other

“Uncommon” does not imply stronger or weaker prior art—it simply flags where discoverability differed.

Comparison of Prior-Art Visibility for Dr. Squatch, LLC v. The Procter & Gamble Company IPR2024-01174

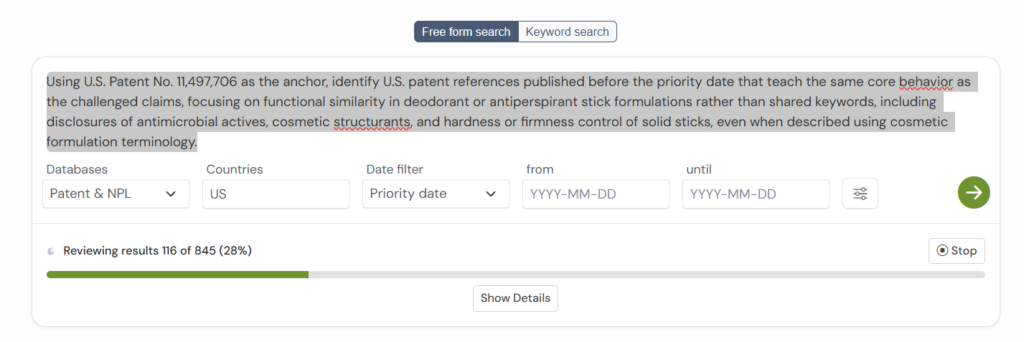

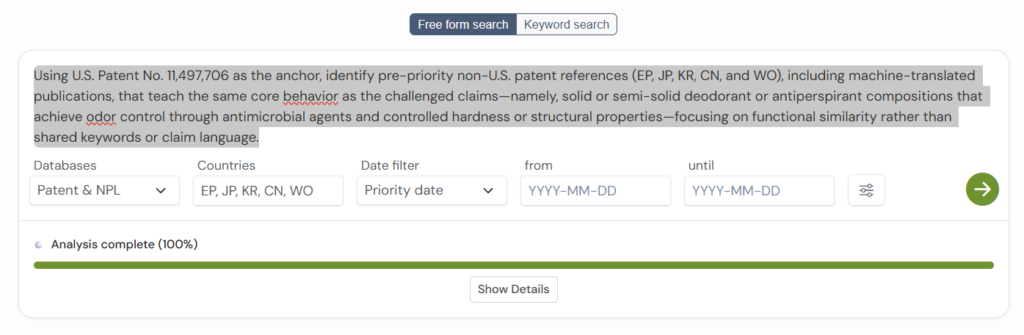

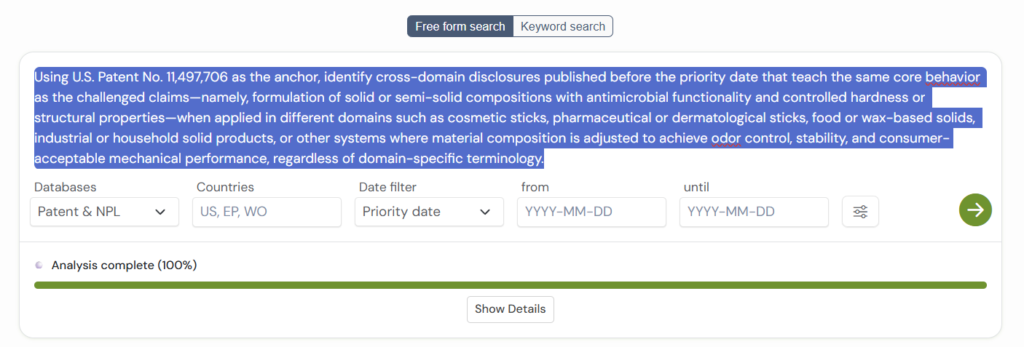

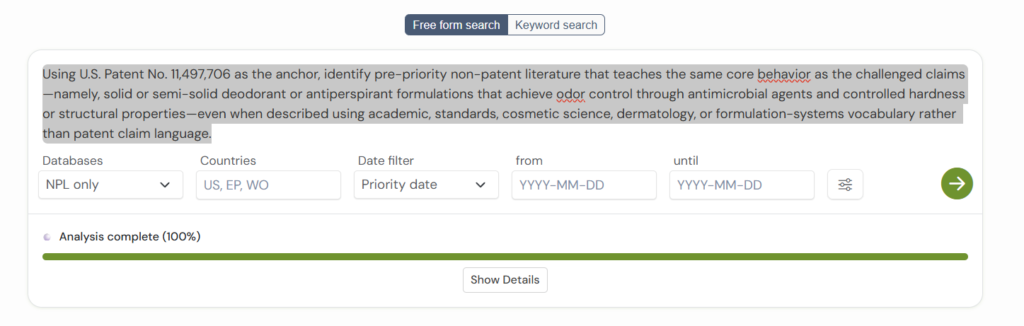

For this second-pass semantic search, we used simple, plain-English queries. We referenced the subject patent number and specified the type of prior art we were looking for to narrow results across different categories. The exact queries are shown in the screenshots below.

U.S. Patent References

Several U.S. patents appear in both the official record and GPS results, reflecting foundational work in cleansing compositions and cosmetic formulations.

However, GPS also surfaced numerous additional U.S. patents—from Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Beiersdorf, Revlon, BASF, and others—that address similar formulation challenges under different framing or ingredient selections.

These disclosures often focus on:

- surfactant structuring,

- sensory optimization,

- bar hardness and wear,

- conditioning additives, and

- formulation stability.

Non-U.S. Patent Filings

Overlap between the official record and GPS results is limited in non-U.S. filings.

GPS broadened visibility into:

- European and WO applications from major cosmetic suppliers,

- Japanese and Chinese filings addressing cleansing performance and ingredient systems, and

- older foreign disclosures that rarely appear in U.S.-centric searches.

This expansion significantly widens the historical and geographic context of the claimed technology.

Cross-Domain References

Cross-domain overlap between the official PTAB record and the GPS results is limited.

Only one cross-domain reference appears in both sources. Other cross-domain disclosures surfaced by GPS do not appear in the official exhibit list.

These additional references address similar formulation principles—such as hardness control, structurant selection, and antimicrobial incorporation—but are framed in adjacent cosmetic stick and personal-care contexts.

Non-Patent Literature (NPL)

No direct overlap appears between the official NPL exhibits and the GPS-surfaced literature.

Instead, GPS highlighted additional cosmetic science publications spanning:

- surfactant chemistry,

- emollient performance,

- skin-barrier interaction,

- formulation stability, and

- ingredient safety and regulatory considerations.

Many of these references predate modern “natural” branding trends but describe the same functional building blocks used today.

Below is the complete table showing how official references and GPS results compare across categories.

| Match | Type | Official (Petitioner’s Exhibits) | GPS |

| Common | US Patents | US4049792A (Ex. 1041)US4919934A (Ex. 1043)US5019375A (Ex. 1083)US5429816A (Ex. 1055)US5976514A (Ex. 1054)US6048518A (“Bianchi ‘518”, Ex. 1006)US6123932A (Ex. 1047)US9314412B2 (“Phinney”, Ex. 1004)US2005142085A1 (Ex. 1014)US2007166254A1 (“Bianchi ‘254”, Ex. 1008) | |

| Uncommon | US Patents | US5585092 (Ex. 1025)US9610237 (Ex. 1026)US10905647 (Ex. 1053)US10966915 (Ex. 1045)US11433018 (“Lesniak”, Ex. 1003)US11497706 (Target Patent, Ex. 1001)US11540999 (Ex. 1082)US20080287377 (Ex. 1060)US20140199252 (Ex. 1027)US20160089321 (“Anconi”, Ex. 1057)US20190000734 (“Sturgis”, Ex. 1056)USRE38141 (Ex. 1062) | US4822603A (Procter & Gamble)US5486355A (Church & Dwight)US5840288A (Procter & Gamble)US7347991B2 (Unilever)US4021536A (Armour Pharma)US6033651A (Revlon)US2009304617A1 (Banowski et al.)US6171601B1 (Procter & Gamble)US5681552A (Mennen Co)US4675178A (Calgon Corp)US2006029624A1 (Banowski et al.)US5916546A (Procter & Gamble)US5194262A (Revlon)US10688028B2 (Procter & Gamble)US2014356304A1 (BASF SE) |

| Common | Cross-domain | US4049792A (Ex. 1041) | |

| Uncommon | Cross-domain | US11433018 (“Lesniak”, Ex. 1003)US9314412 (“Phinney”, Ex. 1004)US6048518 (“Bianchi ‘518”, Ex. 1006)US20070166254 (“Bianchi ‘254”, Ex. 1008)US11540999 (Ex. 1082)US4919934 (Ex. 1043)US5019375 (Ex. 1083)US5429816 (Ex. 1055)US5976514 (Ex. 1054) US6123932 (Ex. 1047)US5585092 (Ex. 1025) US9610237 (Ex. 1026)US10966915 (Ex. 1045) US10905647 (Ex. 1053) | AR040468A1 (Colgate Palmolive)DE3147777A1 (Beiersdorf AG)US2005266034 A1 (Muller et al.)DE202008014407U1 (Beiersdorf AG)US2019000747 A1 (Procter & Gamble)DE102007045241A1 (Beiersdorf AG)WO2008006718A2 (Symrise GmbH)US2011300091 A1 (Dial Corp)DE4237081A1 (Beiersdorf AG)EP1501379A1 (Miret Lab)EP0058474A2 (Unilever)EP0935960B1 (Beiersdorf AG)EP0658097A1 (Beiersdorf AG)EP1537781A1 (Air Liquide Sante)FR2682296A1 (Sederma SA) |

| Common | Non-US | WO2012098189 (Ex. 1015/1049) | |

| Uncommon | Non-US | EP0471392 (Ex. 1072) | WO2002083091A1 (Unilever)JP2014533667 A (Unilever)WO2009101000A2 (Henkel)WO2012088495A2 (Dial Corp)WO2025132032A1 (Unilever)WO2001078658A2 (L’Oreal)WO2021016683A1 (L’Oreal)CN1483394A (Inst. of Radiation Medicine)EP2934459A2 (Beiersdorf AG)WO2012131363A3 (Applisci Ltd)JPH02256609A (Ichikawa)WO1998027954A1 (Procter & Gamble)WO2011029701A2 (Henkel)WO1997016161A1 (Unilever)EP0126944A2 (Dragoco) |

| Common | NPL | None | |

| Uncommon | NPL | Abendrot et al. (2018)Al-Rawi et al. (2018)Aniston (2015)Carvalho (2011)Chen et al. (2014)Corral et al. (1988)Dean (1999)Emanoil (2006)Handley & Burrows (1994)Heisterberg et al. (2011)IFSCC (1998)Khuntayaporn & Suksiriworapong (2017)Laden et al. (1999)Lamb (1946)Lambert (2011) | **Akshatha et al. (2023)Smits et al. (2012)Y et al. (2014)Bok et al. (2024)Celleno et al. (2019)Martini (2010)Li (2003)Rusli (2014)Nurfalah et al. (2024)Shen (2006)GM (2022)Askarov et al. (2022)Bhatt et al. (2021)Ahuja et al. (2024)** |

Viewed through a semantic lens, several themes emerge:

- The core formulation concepts are well established across decades of literature.

- Similar technical solutions appear repeatedly under different ingredient names and functional descriptions.

- Non-U.S. filings and cosmetic science publications materially expand the visible prior-art landscape.

- Without structured, second-pass review, many of these disclosures are easy to miss early on.

This does not mean every reference is legally dispositive, but it does mean they are worth knowing about before positions harden.

Global Patent Search: Strengthening Prior-Art Review with Semantic Second-Pass Analysis

Global Patent Search is designed for the moment when prior art looks complete—but certainty still matters.

GPS does not replace examiner searches, prosecution histories, or legal judgment. It strengthens them by adding a semantic second pass that tests whether critical disclosures may be hidden behind different terminology, older classifications, or adjacent technical framing.

Used after an initial keyword- and classification-based search, GPS helps IP teams:

- move beyond surface-level language and cosmetic branding differences,

- surface technically similar disclosures described using alternative vocabulary,

- identify older, non-obvious, or cross-context references that are easy to miss in first-pass searches, and

- assess prior-art coverage before investing time and resources in deeper legal analysis.

The result is a clearer, more defensible view of the prior-art landscape—one that reduces blind spots early and supports more confident strategic decisions.

Explore Global Patent Search. Take a semantic second look and see what the prior art reveals.

Note: This article is not legal advice. The analysis and tables presented here are based on a preliminary prior-art search conducted using Global Patent Search (GPS) and are intended solely for research and exploratory purposes. Qualified IP counsel should conduct independent searches and apply their own professional judgment for any specific matter.