| TL;DR: Missed prior art is not a search failure. It’s a risk-management failure. The goal is not “more references.” The goal is fewer surprises. And to derisk missed prior art, this checklist serves as a Northstar for patent attorneys, whether it’s for invalidation, PTAB, or any high-stakes litigation, especially for AI and software patents. |

Even highly experienced search teams miss critical prior art when searches stay narrow, rely on limited tools, or fail to explore adjacent technical areas where the same concepts are disclosed.

This risk is especially pronounced in software and AI patents, where the same functionality is often described using very different technical language across domains.

For example, in Jumio Corp. v. FaceTec, Inc. (PTAB, 2025), the winning party relied on a key prior art reference drawn from the image-processing field, not biometric authentication.

The PTAB rejected the argument that the reference was “outside the field,” consistent with Federal Circuit guidance in Netflix v. DivX that analogous art is not confined to a narrowly defined field of endeavor.

Hence, to reduce the risk of overlooked prior art and gain greater confidence in search completeness, we prepared this practical checklist for patent attorneys.

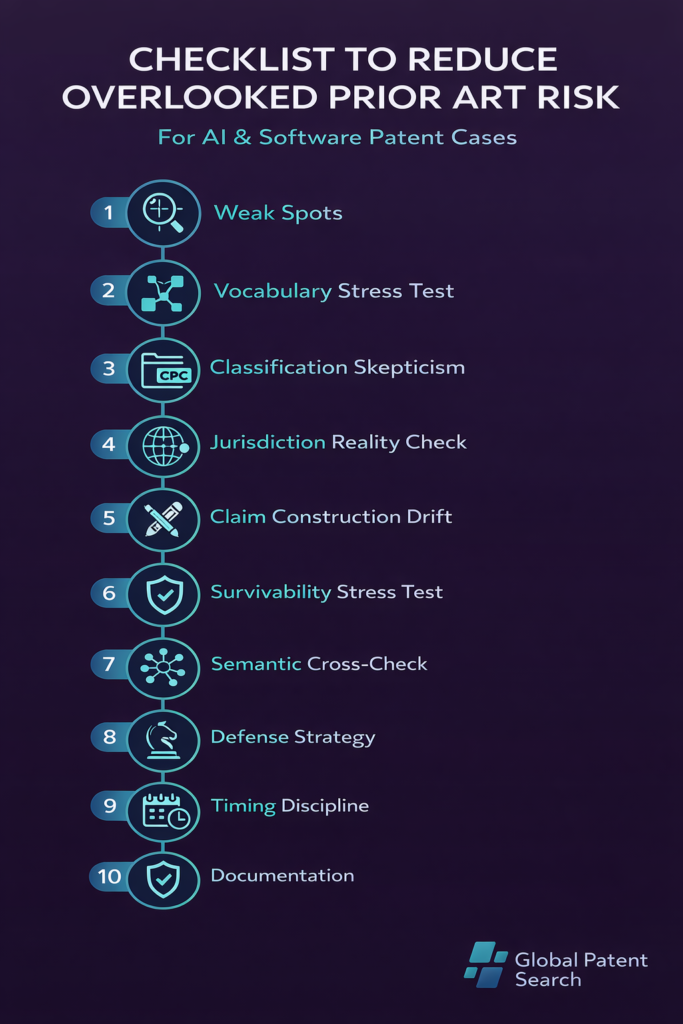

Below is a quick overview, followed by deeper explanations for each step:

- Identify the 2–3 claim elements most likely to be attacked before reviewing vendor results, so the search is anchored to the real weak spots.

- Run a vocabulary stress test to ensure the search did not depend on claim wording and still surfaces cross-phrased prior art.

- Apply classification skepticism by expanding beyond obvious CPC buckets and checking adjacent classes where the same function is commonly filed.

- Do a jurisdiction reality check to confirm meaningful non-US coverage and avoid “global search” that is effectively US/WO only.

- Plan for claim construction drift by validating that your best prior art still maps under broader or alternative constructions.

- Stress-test prior art survivability by asking how each “strong” reference could collapse under scrutiny and why.

- Run a second-pass semantic cross-check focused on function, not wording, to catch out-of-class and cross-domain disclosures.

- Do the opposing-counsel thought experiment to surface embarrassing gaps before someone else does.

- Follow timing discipline by re-checking prior art at the moments that matter, not only at the start.

- Document for defensibility so you can explain how completeness was validated if diligence is questioned.

1. Before You Even Look at the Vendor’s Results

Identify the 2–3 claim elements most likely to be attacked, not the whole claim. Look for the functional parts that appear abstract, broad, or outcome-oriented.

Ask:

- Which element would opposing counsel say is “routine” or “well known”?

- Which element depends most on interpretation?

For instance: In Mobile Acuity, Ltd. v. Blippar Ltd., the court dismissed Mobile Acuity’s patent infringement lawsuit after finding the claims invalid. Rather than looking at the patent as a whole, the court zeroed in on a handful of core steps. It concluded that taking an image, uploading it, linking information to that image, and later retrieving or displaying that information were abstract ideas. The court viewed these steps as routine tasks carried out using standard computer technology.

2. Vocabulary Stress Test (Non-Negotiable)

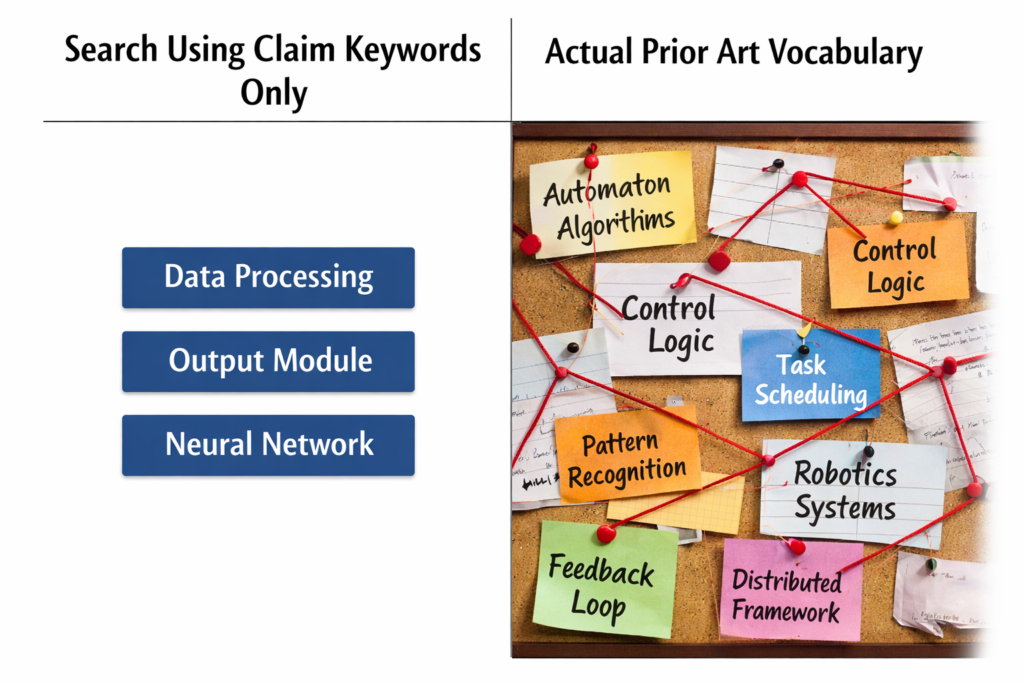

Assume that the best prior art may describe the same functionality using entirely different language. And, hence, focus not only on what things are called, but also:

- Related verbs (what the system does): determine, coordinate, regulate

- System behavior: feedback loops, task scheduling, state transitions

- Adjacent domain language: automation, robotics, middleware

Ask:

- What if the prior art never uses the claim’s words?

- Do most results reuse the claim’s language instead of describing the same function in different ways?

Searchers rarely miss synonyms; what they really miss are the conceptual reframings. Hence, we have prepared a ChatGPT prompt for you to uncover how the same invention is described using entirely different language.

| 📌ChatGPT Prompt for Vocabulary Stress Testing in Prior Art Searches You are assisting with a patent invalidation search. Your role is strictly limited to VOCABULARY STRESS TESTING.You are NOT determining patentability, novelty, obviousness, claim construction,or legal equivalence. Your sole task is to identify terminology, phrasing, and conceptual languagethat could describe the SAME TECHNICAL FUNCTIONS as the given patent,even if the wording is entirely different from the patent’s language. Patent number: [INSERT PATENT NUMBER] Instructions:1. Read the independent claims and the specification.2. Decompose the invention into its core technical functions using verb + object formulations (what the system does).3. After decomposition, intentionally ignore the patent’s preferred terminology. For EACH core technical function, generate terminology under the following categories: A. Functional paraphrases (Different ways to describe what the system does) B. Cross-industry terminology (How other industries or domains might describe the same function) C. Legacy / pre-standard language (Older, early-stage, or non-modern phrasing likely used before terminology stabilized) D. Implementation-agnostic phrasing (Language that avoids architectural, software, or AI-specific assumptions) E. Non-patent / academic / standards-style language (How this function would appear in papers, standards drafts, or technical literature) F. Negative or inverse phrasing (What the system avoids, prevents, eliminates, or mitigates) Do NOT repeat claim language unless strictly necessary for clarity. Output format (follow exactly): Function 1: [Abstract functional description — no claim language] – Functional paraphrases:- Cross-industry terms:- Legacy / pre-standard terms:- Academic / NPL / standards terms:- Negative/inverse phrasing: Repeat the same structure for each major function. Final stress-test:Provide a consolidated list of:1. Terminology that would NOT be captured by searches relying on the patent’s keywords2. Terms likely to appear in different or neighboring CPC subclasses3. Terms more commonly found in non-patent literature than in patent filings |

Alternatively, run the subject patent through Global Patent Search to stress-test your prior art coverage. Its AI-powered semantic search can surface relevant references that keyword-driven searches may miss due to vocabulary differences.

3. Classification Skepticism Check

Do not assume CPC (Cooperative Patent Classification) coverage equals completeness, especially for modern software claims.

Ask:

- Did the search go beyond obvious AI and software classes such as G06F and G06N?

- Did the search include adjacent classes where the same behavior is often implemented, such as:

For instance: In the Tesla, Inc. v. Autonomous Devices, LLC (PTAB 2024–2025), claims were held obvious over prior art describing the training and operation of robotic devices and shared robot knowledge bases, illustrating that decisive prior art may lie in robotics/automation domains, not just obvious software/AI classes.

4. Jurisdiction Reality Check

Do not assume a “global search” means meaningful non-US coverage, especially for software and AI patents.

Ask:

- Did the search go beyond U.S and WO publications in substance, not just in labels?

- Was Chinese prior art reviewed beyond abstracts, including full specifications where key implementation details often reside?

- Were foreign filings using different technical framing or terminology meaningfully considered?

- Did translation quality limit what was actually reviewed?

As noted by National Law Review, US-centric patent searches increasingly expose litigants to risk as innovation accelerates globally, with overlooked foreign prior art becoming a recurring weak point in high-stakes disputes.

This risk of missed prior art is amplified in software and AI, where recent data reported by Reuters shows China filing more than six times as many generative AI patent applications as the US, underscoring that critical technical disclosures often originate outside U.S jurisdictions.

5. Claim Construction Contingency

Assume claim construction will shift.

Ask:

- If the claim is read broader, does our prior art still map?

- If a term is construed functionally, do we still have coverage?

As highlighted in the IPWatchdog Patently Strategic podcast on claim construction, courts interpret claim language in ways that often shift how a patent’s scope is understood. This understanding can make or break a case long before final judgment, further underscoring the need to stress-test prior art under multiple plausible constructions.

6. Prior Art Survivability Test

A reference can look perfect in a chart and still fall apart later. Stress-test “strong” art the way opposing counsel, the PTAB, and the Federal Circuit will.

Ask:

- Does the reference only work for one narrow implementation?

- Does your mapping depend on assumptions an expert could realistically challenge?

- If this is a combination, is the motivation to combine clearly explained and supported by the record?

For instance: In Palo Alto Networks v. Centripetal Networks, the Federal Circuit sent the case back because the reasoning behind combining prior art references was not clearly explained. The takeaway is simple: even when references seem to fit, weak or under-explained reasoning can cause the entire argument to fail later.

7. Second-Pass Semantic Cross-Check

Always verify the first search. After keyword and CPC-based searching, run an intent-based semantic search focused on function, not wording.

Purpose:

- Surface prior art that describes the same behavior using different terminology

- Catch references outside expected classes or technical vocabularies

Tools like Global Patent Search work best as a second-pass verification layer, helping uncover semantically related prior art that keyword-driven searches often miss.

Let’s give it a try!

For this demonstration, we selected a live PTAB proceeding where non-patent literature already plays a visible role:

Case: Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. v. VB Assets, LLC

Proceeding: IPR2025-00869

Subject Patent: U.S. Patent No. 8,886,536

Using three semantic queries, we used GPS to surface not only U.S. patents, but also relevant non-patent literature, cross-domain disclosures, and non-US references.

Several key references cited in the official record also appeared in the GPS results, while additional references surfaced as shown in the table below:

| Match | Type | Official | GPS |

| Common | US Patents | US7,609,829 (Wang)US6,513,006 (Howard) | |

| NPL | McTear (2004) — Spoken Dialogue TechnologyO’Neill et al. (2004) — Cross Domain Dialogue Modelling (2004)Seneff et al. (2002) — GALAXY / Mercury Architecture | ||

| Cross-Domain | From Toys and Entertainment – JP2000325669A – “Voice recognition interactive doll toy…” (Kankoku Ekishisu KK) From Vertical Transport (Building Control) – JP2002104745A – “A voice-controlled position-savvy elevator…” (Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV) | ||

| Uncommon | NPL | Bernsen et al. (1998) — Designing Interactive Speech Systems (Springer) Huang et al. (2001) — Spoken Language Processing (Prentice Hall) Kehler (1993) — The Effect of Establishing Coherence in Ellipsis and Anaphora Resolution (ACL) Möller (2005) — Quality of Telephone-Based Spoken Dialogue Systems (Springer) | Bernsen et al., 2002 — Principles for the Design of Cooperative Spoken Human-Machine Dialogue Larsson & Traum (2000) — Information state and dialogue management in the TRINDI dialogue move engine toolkit Möller et al. (2005) — Evaluating the speech output component of a smart-home system Nakano et al. (2000) — Agent-based adaptive interaction and dialogue management architecture |

| Cross-Domain | From Linguistics and Philosophy – H.P. Grice, “Logic and Conversation” (1975) From Online Advertising and Marketing – Joe Plummer et al., “The Online Advertising Playbook” (2007) | From Medical Systems (Endoscopic Surgery) – JP2002123292A — “System Control Device” (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd.) From Vending Machine Application – JPH02250095A — Speech Recognition System (Matsushita Cold Machinery Co. Ltd. / Matsushita Refrigeration) | |

| Non-US | The Petitioner relies exclusively on U.S. patent references, hence nothing exclusive found here. | EP1669846A1 — Dialoging Rational Agent and Intelligent Dialogue Control (France Télécom) JP2006018028A — Dialogue Method and Dialogue Device (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone) KR100768731B1 — VoiceXML-Based Dialogue Flow Control Using Speech Acts WO2003038809A1 — Mixed-Initiative Human–Machine Dialogue Management (Loquendo) | |

8. “Opposing Counsel” Thought Experiment

Assume opposing counsel is looking where you did not.

Ask:

- What source would opposing counsel check first that we ignored?

In software and AI cases, this is often Non-patent Literature (NPL). As observed by Greg Aharonian on IPWatchdog, many software patents cite little to no technical literature, even though key disclosures frequently appear outside the patent record.

Patent analysts observe that over half of software patents cite no NPL at all, despite a rich body of prior art in areas such as machine learning, computer vision, and AI systems (e.g., IEEE, ACM, SPIE publications, technical standards, and open technical documentation).

This mismatch suggests many software patents are vulnerable to NPL-based invalidity attacks, even if those references are rarely spotlighted in public decisions.

9. Timing Discipline

The case isn’t static, nor is the prior art. In patent disputes, the role and strength of prior art often change as a case moves from district court → PTAB/IPR → Federal Circuit.

Re-check prior art at these moments:

- After claim construction briefing: Changes in claim scope can elevate previously marginal references or weaken earlier mappings.

- Before filing an IPR: PTAB standards differ from district court. Prior art must be reframed and sometimes replaced to meet institution thresholds.

- Before expert reports: Expert analysis frequently exposes gaps or assumptions that require additional art.

- Before settlement discussions: Newly surfaced prior art can materially alter leverage and risk assessment.

For instance: In Qualcomm Inc. v. Apple Inc., during the underlying IPR proceedings, Apple relied in part on applicant-admitted prior art (AAPA) alongside other prior art patents and printed publications in its invalidity grounds. The PTAB initially agreed, but on appeal, the Federal Circuit held that specific uses of AAPA did not qualify as “prior art consisting of patents or printed publications” under 35 U.S.C. § 311(b), vacating the Board’s finding and remanding for a fresh determination of whether the petitions met statutory requirements.

10. Documentation & Defensibility

A strong search is not enough. You must be able to defend how you validated it. This matters during cross-examination, PTAB panel questions, and when opposing counsel argues the search was incomplete.

Preserve a clear record explaining:

- Why were additional searches or checks run

- Which avenues were considered and ruled out

- How potential coverage gaps were identified and addressed

Senior patent litigators often emphasize that courts and the PTAB care less about perfection and more about reasoned diligence. A documented, explainable search strategy is far easier to defend than an undocumented one, even if both parties miss the same reference.

There is a widely accepted principle among patent litigators:

| “If you can’t explain why you didn’t find it, the problem isn’t the art — it’s the process.” |

Most items on this checklist are about judgment, strategy, and experience, things only a patent attorney can do well.

But a few steps are tough to execute consistently with traditional tools alone. In particular, vocabulary stress testing, cross-domain discovery, and second-pass semantic verification are where new-generation AI tools, like GPS, add real leverage without replacing legal judgment.

Global Patent Search – An AI-Powered Search Tool to Minimize Overlooked Prior Art Risk

Global Patent Search is designed for one specific purpose: reducing missed-art risk in high-stakes patent work. It does not replace professional search judgment or vendor reports. It acts as a verification layer where traditional searches are most likely to break down.

The patent attorneys who have used GPS have especially appreciated the speedy claim chart generation with color-coded element mapping, making it a must-try tool!

If the cost of overlooked prior art is high, a second-pass search should not be optional.

Use Global Patent Search to verify what your first search may have missed — before opposing counsel finds it.

Frequently Asked Questions

- How to Speed Up Claim Chart Generation Using AI?

While AI can speed up claim chart preparation, generic AI tools are not built for patent work. They often miss claim structure, blur element boundaries, and create extra review overhead.

Purpose-built tools like the claim chart generator from the suite of Global Patent Search tools speed things up in three practical ways:

- Claim element extraction: Breaks claims into chart-ready limitations.

- Color-coded element mapping: Visually links each claim element to supporting passages in the prior art.

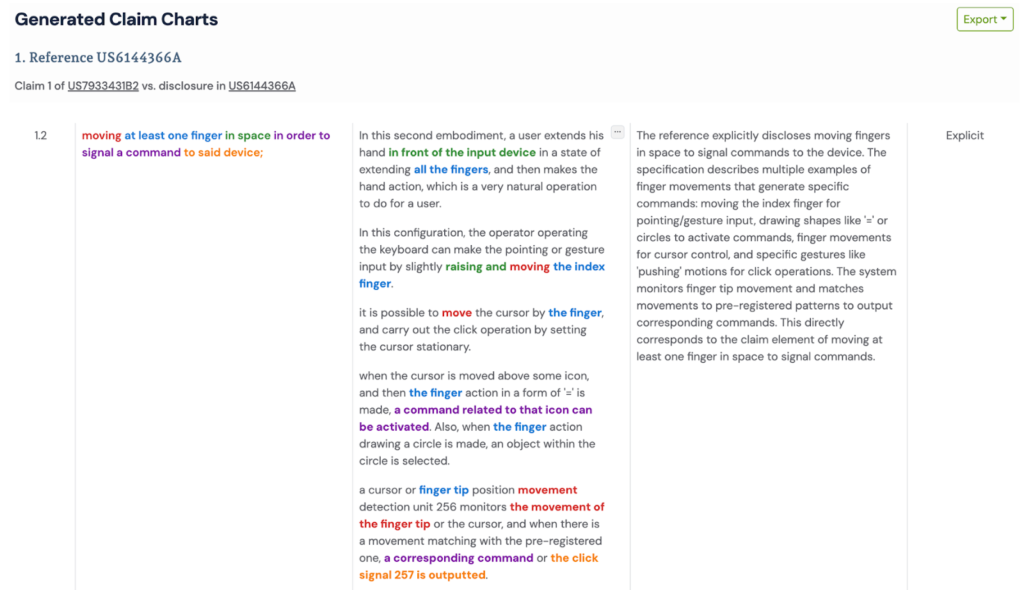

For example, in Apple Inc. v. Gesture Technology Partners, LLC, only claim element mapping for claim 1.2 from U.S. Patent No. 7,933,431 is shown below. The element is mapped against the key prior art U.S. Patent No. 6,144,366 (Numazaki).

- Review-first drafts: Produces a structured draft for refinement, not rework.

The result is less manual effort and more time spent on legal analysis and strategy.

- What’s Considered a PTAB Procedural Error?

A procedural error occurs when the PTAB’s handling of an IPR deprives a party of fair notice or a meaningful opportunity to respond.

Common examples include:

- Denying a party the opportunity to respond to a new claim construction

- Relying on grounds or reasoning not raised adequately during the briefing

- Shifting theories between institution and the final written decision without notice

- Refusing to consider responsive arguments tied to the Board’s own interpretations

3. What Tactics Improve PTAB Appeal Outcomes?

Based on recent PTAB appeal practice, successful appeals commonly apply the following tactics:

- Lead with your strongest technical argument. Pick the clearest claim-vs-prior-art mismatch, supported by Federal Circuit or PTAB precedent.

- Anchor arguments strictly to claim language. Focus on what the claims actually require, not examiner assumptions or invention benefits.

- Use dependent claims strategically. Well-crafted dependent claims can expose examiner error and create alternative reversal paths.

- Directly attack flawed examiner reasoning. Clearly explain why the examiner’s conclusions lack evidentiary or logical support.

- Always file a Reply Brief. Use it to rebut new arguments in the Examiner’s Answer and reinforce your strongest points.