Google vs EcoFactor has been in the news for quite a while now. At the center of the patent dispute lies a smart-home patent, which was found to be infringed. While the court awarded $20 Million to Ecofactor, that aspect of the ruling remains under challenge.

However, our curiosity lay elsewhere.

Google Nest and other smart-home platforms sit at the intersection of utilities, HVAC systems, cloud software, and data-driven control. Companies across these domains have been experimenting with demand response and energy management for decades, including newer climate-focused AI platforms.

We wondered, how did this idea emerge in such a crowded and mature technology landscape?

So we put the Global Patent Search platform to work. Before getting into what we found, let us first understand what this patent actually covers.

Understanding US Patent 87,38,327 B2

Let me start with what the patent is not. US8738327B2 is not about inventing a new thermostat or a new way to turn air conditioners on and off. The patent US8738327B2 covers what happens after a demand response event is triggered. That is, it verifies whether or not peak demand reduction actually happened.

As with any smart home, the setup is standard. A thermostat sits inside a home and controls the HVAC system. That thermostat continuously reports indoor temperature data to a remote server over a network. Separately, the server also receives outside temperature data from external sources, such as weather services tied to the geographic location, like ZIP codes.

These two streams of information, i.e, inside temperature and outside temperature, form the foundation of the system.

What the system does next is the key idea. Over time, the server learns how a specific building typically behaves when outside temperature changes. Every building heats up or cools down at its own pace, depending on factors like insulation, size, and construction.

By observing past temperature patterns, the system can estimate how quickly the indoor temperature should change under different conditions.

Now, when a demand-response event occurs, the system does not rely on a simple confirmation signal or a meter reading. Instead, it watches how the indoor temperature actually changes and compares it to what the model expects, placing US8738327B2 in the same behavioral-verification lineage as US8037161B2. The latter patent reflects a broader shift in home-network design toward verification based on observed behavior rather than static device declarations.

Coming back to the patent in case, if the temperature follows the expected pattern, the system concludes that the building responded as intended. If it does not, the system can detect that something was different from what was expected.

In practical terms, the patent covers a way for utilities to verify participation in demand-response programs using temperature behavior, rather than assuming compliance or installing additional hardware.

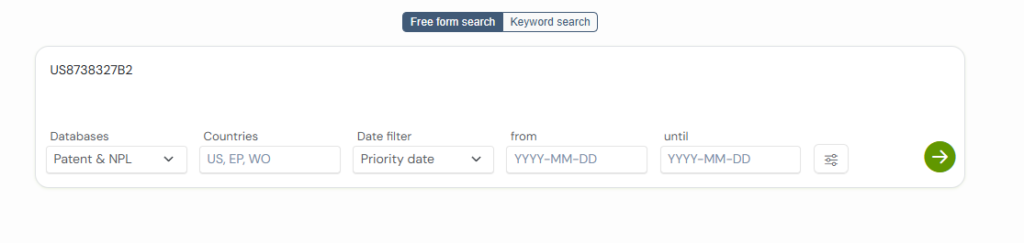

Putting the Patent to the Test with Global Patent Search

To understand the technology landscape around this patent, we put Global Patent Search to work. We started by entering the patent directly into the platform. GPS allows both free-form searches and direct patent-number inputs that automatically expand into a full technical query.

Source – Global Patent Search

Since this patent traces back to provisional filings from 2007, the system automatically set the priority-date cutoff to 2007. That search surfaced over 400 results across patent and non-patent literature, spanning utilities, HVAC systems, and demand-response research.

Among the patents reviewed, a few clear patterns emerged:

- Several patents focused on direct control systems. In these approaches, utilities issued commands to thermostats or HVAC units to reduce load. Once the control signal was sent, compliance was largely assumed. For example, Honeywell’s early load-shedding patent, US4345162A, adjusted HVAC operating cycles during peak periods by issuing control instructions. Once those instructions were sent, the system assumed the desired reduction had taken place.

- Some patents relied heavily on metering and instrumentation. These systems used sensors, runtime logs, or hardware measurements to assess demand reduction. Verification here depended on additional equipment rather than observed behavior.

- A number of references took a statistical or planning-led approach. These focused on analyzing how temperature and electricity load behaved at an aggregate level. For instance, the Taipower load-management analysis focused on understanding how electricity demand changed with temperature across customer groups. Models like these helped utilities plan demand-response programs.

- Others explored coordination-based systems. These patents managed multiple air-conditioning units together across homes or buildings. Even here, the emphasis remained on coordinating control, not on verifying what actually happened inside a structure.

What Did the Sort by Relevance Feature Reveal?

While there were 400+ references across patents and non-patent literature, we wanted to understand the patents that had some kind of meaningful overlap with US8738327B2. So we applied the sort by relevance feature on the GPS tool.

This narrowed the field to 11 key references across both patents and non-patent literature.

From these, we identified five patents worth exploring further, as they offer insight into how the technology evolved leading up to the patent now at the center of this dispute.

US201063634AI – Monitoring Utility Delivery Inside Multi-Unit Buildings

This patent application, US2010163634A1, focused on a problem common in apartment buildings with centralized heating or cooling.

That is, knowing whether each unit actually receives the utility it requests, and whether that usage is legitimate. At its core, the system monitors utility usage at the level of individual apartments or zones within a building. It does this by tapping into existing thermostat wiring, which makes installation easier and avoids the need for major retrofits.

Each unit has sensors that track air temperature near the thermostat, the thermostat’s on or off state, and the temperature of pipes that deliver heating or cooling to that unit.

The system monitors each unit using a combination of thermostat state, indoor air temperature, and supply pipe or duct temperature. By recording how long a thermostat remains active and comparing that to temperature changes in both the room and the supply lines, the system creates a usage audit for every unit.

That is where this patent goes beyond basic monitoring. It explicitly looks for anomalies and tampering, such as tenants manipulating thermostats or leaving windows open to defeat system limits. The patent also defines different fault types, including supply faults, limit violations, and suspected tampering, and generates alerts when these conditions appear.

This patent, just like the US’327 patent relies on verifying behavior rather than assuming compliance. This patent does so using direct sensing, runtime logging, and physical infrastructure data inside the building.

In that sense, US2010163634A1 reflects an earlier, hardware-centric approach to verification. A version that focuses on measuring what happened, rather than inferring it from thermal behavior.

JP2003106603A – Peak Power Cut Using Network-Controlled Air Conditioners

JP2003106603A, filed by Sanyo Electric in 2001, addressed a related but distinct problem in the demand-response landscape. That is, how electric utilities can actively reduce peak power consumption during periods of high grid stress.

The system uses a network to exchange signals between an electric power company and customers who have agreed to participate in peak power cut programs. When the power company determines that demand is approaching a critical level, it transmits a peak-cut request signal to specific customers over the network.

At the customer side, a home server receives this signal and instructs a control device to change the air conditioner’s set temperature in a direction that reduces power consumption.

The system also sends information back to the power company confirming that the peak-cut operation was executed, enabling discounts or incentives to be applied.

Crucially, JP2003106603A assumes that once the control signal is executed, the intended demand reduction has occurred.

The Sanyo patent probably inspired the idea of using network-connected systems and utility-driven demand-response events.

US5816491A – Early Demand-Response Control and Measurement Using Thermostats

The GPS tool also surfaced some patents dating to the late 1990s. One of them was US5816491A, filed in 1996, which represents an early generation of demand-response systems.

This patent described a system where utilities directly controlled HVAC operation during peak periods.

The system worked by inserting a control and measurement device into the low-voltage thermostat wiring. This device records thermostat on and off signals, indoor temperature, and the duration of fuel-on states. During peak load intervals, the control unit restricts cumulative on-time to a predefined limit, turning HVAC systems off once that limit is reached.

Crucially, the patent also measures what happens after control is applied. It records runtime and temperature data so utilities can evaluate how effective the load reduction was.

US5816491A can be considered an early predecessor to the subject patent, as it uses thermostat-level data for post-event assessment.

From Claims to Context: What Global Patent Search Makes Visible

Stepping back to the Google vs EcoFactor dispute, what stood out to us was not just the outcome of the case, but the depth of technology that surrounds this patent.

Smart-home platforms like Google Nest operate at the intersection of different technologies, relying on smart-home communication layers that translate across incompatible device protocols and network formats. That makes understanding the underlying patent landscape especially important.

This is where tools like Global Patent Search become valuable.

By starting with the subject patent and tracing earlier work across patents and non-patent literature, GPS helps surface how ideas evolved, what approaches were tried before, and where a given patent fits within that progression.

This kind of analysis can also help identify prior art that may warrant closer legal scrutiny, though it does not replace formal invalidation analysis or expert legal review.

In this instance, the GPS results suggest that US8738327B2 builds on decades of demand-response research while introducing a distinct verification layer. That depth and differentiation may help explain why the patent has held up under challenge so far.

It remains to be seen how the broader dispute over the demand amount evolves. But as a case study, this patent illustrates how careful landscape analysis can clarify not just what a patent claims, but why it matters.

If you are exploring similar questions, the Global Patent Search tool offers a practical starting point for uncovering that context. Try the tool here!

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a demand-response system, and why do utilities use it?

A demand-response system allows electric utilities to reduce power consumption during peak periods by influencing how and when customers use energy. Instead of building new power plants, utilities temporarily reduce load, often by adjusting HVAC operation, to keep the grid stable during high-demand hours.

2. How is verification different from simply controlling HVAC systems?

Control focuses on sending a command, such as changing a thermostat setting. Verification checks whether the intended outcome actually occurred. Instead of assuming compliance, verification looks at measurable effects, such as temperature behavior, to confirm that demand reduction truly happened after the control event.

3. How were demand-response systems implemented before smart thermostats and cloud platforms?

Earlier systems relied on direct hardware control. Utilities cycled HVAC systems on and off using timers, relays, or low-voltage thermostat controls. Some systems logged runtime data, but most assumed that load reduction occurred once control signals were executed, with limited post-event validation.

4. Why is post-event verification important for utility demand-response programs?

Without verification, utilities cannot reliably know whether demand-response actions worked. Post-event verification provides evidence that load reduction actually occurred. It also improves program accountability, supports incentive mechanisms, and reduces reliance on assumptions or additional hardware installations.