Imagine trying to talk to several people at once in a narrow hallway. You cannot make the hallway wider, but you still need everyone to hear the message clearly. That is exactly the problem many wireless systems face when bandwidth is limited.

US7864900B2 approaches this differently. Instead of sending one signal at a time, it sends a small set of carefully chosen frequencies together. Each set stands for a chunk of data. The receiver simply listens for which frequencies arrived and converts that pattern back into information. This way, more data fits into the same narrow space without adding noise or complexity.

This patent is currently involved in CommPlex Systems LLC v. Cambium Networks, Inc. To understand where this idea came from, we used Global Patent Search tool to trace earlier inventions that explored similar ways of sending data using multiple frequencies.

How This System Sends More Data Without Asking for More Bandwidth

Think of older wireless systems like a single delivery bike. Every time you want to send more packages, you either make more trips or add more bikes. Both options cost more and slow things down. US7864900B2 takes a different route.

Instead of sending one signal for one piece of data, this system sends multiple tiny signals together, each at a slightly different frequency.

The trick is that these frequencies are carefully spaced so they do not interfere with each other. Each unique combination of frequencies represents a specific set of bits, much like choosing a specific group of keys on a piano to play a chord instead of a single note.

Before sending real data, the system first sends a short calibration signal. This helps the receiver understand any small shifts that happen during transmission. Once calibrated, the receiver listens, identifies which frequencies arrived, and simply looks up what data that combination represents. By doing this, the system fits more information into the same narrow bandwidth, without adding extra hardware or power.

Key Ideas Behind the Communication System

At its core, this patent focuses on sending more data through limited bandwidth without making the system heavier or more complex.

- Data is sent as frequency groups, not single signals: Instead of using one frequency per bit, the system sends small combinations of frequencies together. Each combination represents a specific piece of data.

- Frequencies are carefully spaced to avoid interference: All frequencies are orthogonal, which means they do not overlap or disturb each other, even when sent at the same time.

- A short calibration step corrects small frequency shifts: Before real data is sent, the system adjusts itself so the receiver knows exactly what to listen for, even if conditions change.

- The receiver uses simple signal processing to decode data: Techniques like FFT and lookup tables help the receiver quickly identify which frequencies were sent and convert them back into information.

- Higher data rates with less hardware and power: Because multiple signals are processed together, the system reduces processing load while increasing data density per unit of bandwidth.

Together, these features show how the patent rethinks narrowband communication by making smarter use of frequencies rather than adding more spectrum.

A similar philosophy appears in carrier aggregation systems such as those described in EP2525515B1, where multiple frequency components are coordinated to improve data reliability and efficiency without expanding the available bandwidth.

Five Earlier Patents That Pointed in the Same Direction

US7864900B2 did not appear in isolation. The idea of sending more data through limited bandwidth evolved through many smaller steps, each solving a specific part of the problem.

Some focused on frequency spacing, others on decoding signals more reliably, and a few on reducing hardware complexity.

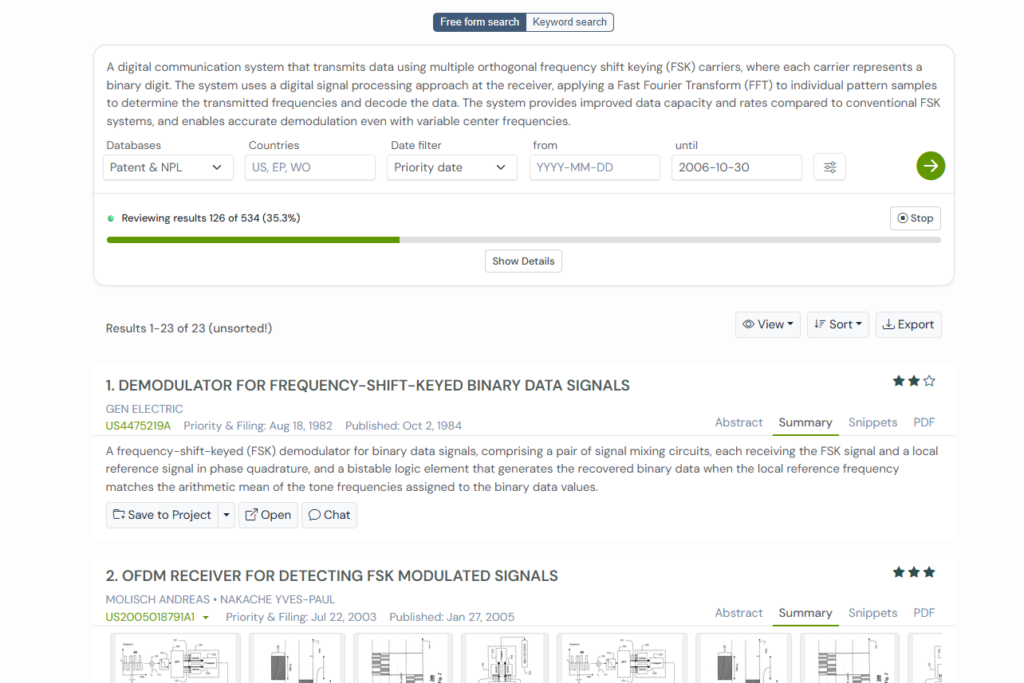

To understand how this approach took shape over time, we used the Global Patent Search platform to look back at earlier patents working in similar areas.

Let’s look at five earlier patents that explored ideas closely related to this system.

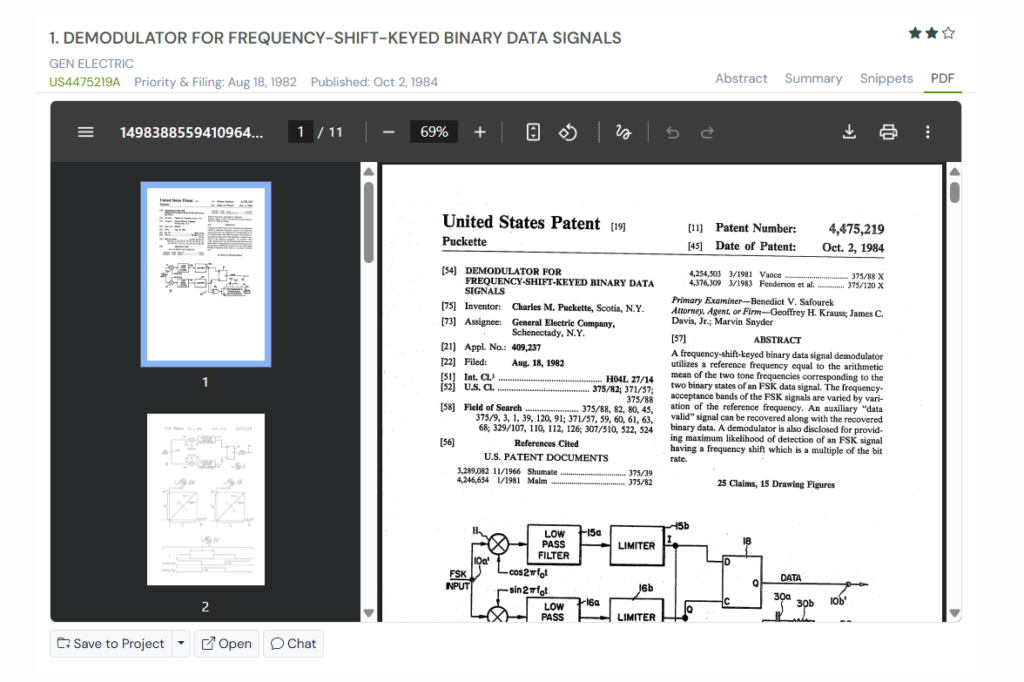

1. US4475219A

Filed in the early 1980s, US4475219A focuses on a very practical problem. When data is sent using frequency shifts, the receiver has to correctly decide which frequency was transmitted. At the time, many demodulators could do this, but they were expensive, hard to tune, and not easy to integrate into compact hardware.

This patent introduces a cleaner way to demodulate binary FSK signals by using two reference signals that are slightly offset in phase. By comparing how the incoming signal aligns with these references, the receiver can reliably decide whether a high or low frequency was sent. The design also allows the operating frequency range to be changed simply by adjusting a reference frequency, instead of redesigning the hardware.

This idea connects to US7864900B2 through its focus on frequency-based data detection and receiver-side efficiency. While US4475219A works with one frequency at a time, it helped establish reliable frequency decoding techniques that later systems could extend to handling multiple frequencies simultaneously.

Why It Matters in the Larger Ecosystem

This patent laid groundwork for flexible, low-cost frequency demodulation. It showed how smart signal processing at the receiver could reduce hardware complexity.

Related ideas around receiver-side decision making also appear in beam-based systems. These were the ones described in EP3469722B, where devices evaluate multiple signal candidates in parallel and report only the most relevant ones to improve overall connection quality.

2. US2005018791A1

By the early 2000s, wireless systems were becoming more complex. Signals were no longer confined to one narrow frequency. Instead, they were spread across many tones, especially in OFDM-based systems. The challenge was clear. How do you reliably detect frequency-based data without building separate hardware for every possible tone?

US2005018791A1, filed in 2003 by Mitsubishi Electric Research Laboratories, takes advantage of something receivers were already doing. Instead of using multiple local oscillators to check each frequency, it uses a Fast Fourier Transform. The FFT breaks the received signal into frequency bins, making it easy to see where the energy is concentrated. The receiver then groups these frequency bins and compares their energy levels to decide which data symbol was sent.

Why It Matters in the Larger Ecosystem

This patent helped bridge traditional FSK signaling with modern FFT-based receivers. It showed that complex frequency patterns could be decoded efficiently using shared signal-processing blocks.

A different branch of communication research looks less at how signals are encoded and more at how networks decide who should be served and when. That perspective shows up in systems like US10694399B1, which focus on directing communication toward specific devices through beam control and localized decision-making.

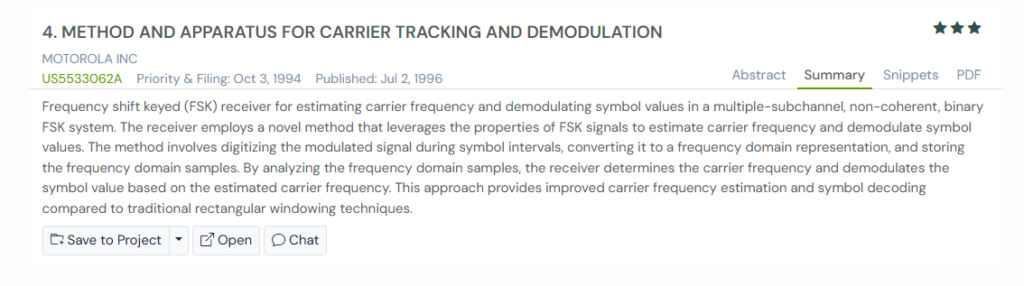

3. US5533062A

As wireless systems grew more crowded, one problem kept showing up at the receiver. Even small shifts in carrier frequency could confuse the system and lead to decoding errors. This was especially true for FSK signals, where data is defined by small frequency changes around a carrier.

US5533062A filed by Motorola in 1994, focused on helping the receiver stay “locked in” to the correct carrier frequency.

Instead of guessing based on a single snapshot, the system looks at multiple signal intervals, converts them into the frequency domain using FFT, and combines their energy patterns. By doing this, the receiver can estimate where the true carrier sits, even if noise or symbol imbalance is present.

Once the carrier position is known, the receiver measures energy at expected frequency offsets and decides which symbol was sent. This approach connects directly to US7864900B2, which also relies on FFT-based frequency analysis, calibration, and energy detection to correctly decode frequency patterns.

Why It Matters in the Larger Ecosystem

The patent showed how careful frequency tracking at the receiver can dramatically improve reliability. Its use of FFTs, zero-padding, and energy-based decisions helped shape later systems that decode multiple frequencies accurately, even in narrowband and noisy environments.

Similar efficiency-driven thinking appears in baseband decoding designs like those described in US6813742B2, where receiver architectures are optimized to process more data per cycle while keeping power consumption low.

4. EP0853853A1

As data rates increased, engineers started realizing that relying on a single carrier was limiting. Different parts of the frequency spectrum behaved differently. Some ranges were noisy, others were clean. Treating the entire band as one block meant performance was always held back by the worst part.

EP0853853A1 published in 1998, introduces the idea of splitting data across many smaller carriers, often called sub-channels. Each sub-channel can carry its own portion of the data, and the system can even adjust how much data each one carries based on noise or interference. If a certain frequency range becomes unreliable, the system simply avoids it.

The transmitter and receiver use FFT and inverse FFT to move between time and frequency domains efficiently, instead of relying on large banks of individual modulators. This connects closely to US7864900B2, which also depends on FFT-based processing and careful frequency selection to improve data efficiency.

Why It Matters in the Larger Ecosystem

This work helped normalize multicarrier thinking. It showed that smarter use of frequencies, rather than wider bandwidth, could unlock higher data rates.

5. US4027266A

In the mid-1970s, most FSK receivers still relied heavily on analog circuits. These designs worked, but they were sensitive to noise, drift, and component variation. Engineers wanted a cleaner and more stable way to decide whether a received signal represented a “0” or a “1”.

US4027266A, filed in 1976, moves that decision process into the digital domain. Instead of comparing raw frequencies directly, the system converts both the reference signal and the incoming FSK signal into digital in-phase and quadrature components. By tracking how the phase difference between these signals changes over time, the receiver can tell whether the frequency is shifting up or down. It then averages these observations to make a reliable bit decision.

This approach connects to US7864900B2 through its use of digital signal processing to interpret frequency behavior, rather than relying on purely analog detection. While this patent works with a single frequency shift at a time, it establishes digital techniques that later systems expand to handle multiple frequencies and higher data density.

Why It Matters in the Larger Ecosystem

This patent helped push FSK demodulation toward digital processing. That shift made receivers more stable, more accurate, and easier to scale.

How These Patents Compare to US7864900B2

Looking at these patents side by side makes the progression very clear. Each one solves a specific piece of the communication puzzle. Some focus on decoding frequency shifts reliably, others on using FFTs to simplify receivers, and a few on spreading data across multiple carriers.

The table below summarizes how each earlier patent connects to the core ideas behind US7864900B2.

| Patent | Core Focus | How It Relates to US7864900B2 | Key Contribution |

| US4475219A | Reliable demodulation of binary FSK signals | Shares the goal of accurate frequency-based detection at the receiver | Introduced flexible, low-cost demodulation using phase-offset reference signals |

| US2005018791A1 | Detecting FSK symbols using FFTs in OFDM receivers | Uses FFT-based frequency analysis similar to US7864900B2 | Showed that frequency patterns can be decoded efficiently without separate hardware per tone |

| US5533062A | Carrier tracking and symbol demodulation using FFT | Aligns with calibration and energy-based decoding in US7864900B2 | Improved reliability by estimating carrier position across multiple symbol intervals |

| EP0853853A1 | Multicarrier modulation using FFT and IFFT | Supports the idea of splitting data across many frequencies | Normalized multicarrier thinking and adaptive use of frequency spectrum |

| US4027266A | Digital FSK demodulation using phase comparison | Early step toward DSP-based frequency interpretation | Shifted FSK decoding from analog circuits to digital processing |

Seen together, these patents show how communication systems gradually moved away from single-frequency, analog-heavy designs toward digital, multi-frequency architectures like the one described in US7864900B2.

How Global Patent Search Helps Make Sense of Patents Like This

When you read communication patents one by one, it’s hard to see how ideas actually evolved. Each document focuses on a narrow problem, and the bigger picture often gets lost in technical detail.

That’s where Global Patent Search tool helps. It brings related inventions together so you can understand how a concept developed over time, not just how one patent describes it.

How to use GPS effectively:

- Enter a patent number and instantly find technically related patents in the same space.

- Review short summaries to quickly understand what each patent is trying to solve.

- Open full documents only when you want to compare specific signal flows or receiver logic.

- Sort results by relevance to focus on themes like multi-frequency signaling or FFT-based decoding.

- Follow earlier references to see how ideas evolved before reaching modern designs.

GPS turns scattered patent documents into a connected technical story.

If you want a faster and clearer way to explore how communication technologies developed, try the Global Patent Search tool today and see the full landscape in minutes.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice. The related patent references mentioned are preliminary results from the Global Patent Search tool and do not guarantee legal significance. For a comprehensive related patent analysis, we recommend conducting a detailed search using GPS or consulting a patent attorney.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why is sending data in limited bandwidth such a big challenge?

Limited bandwidth means there is very little room to separate signals clearly. When more data is pushed into a narrow frequency range, signals can overlap, noise has a bigger impact, and error rates increase. The challenge is to improve data speed without widening the spectrum or adding complex hardware.

2. How does using multiple frequencies improve data transmission?

Using multiple frequencies allows data to be represented as patterns instead of single signals. Rather than sending one bit per frequency, combinations of frequencies can represent more information. This improves data density and efficiency, especially in narrowband systems where expanding bandwidth is not an option.

3. What role does FFT play in modern wireless receivers?

FFT helps receivers analyze incoming signals in the frequency domain. It breaks a signal into frequency components, making it easier to detect which frequencies are present. This allows receivers to decode multi-frequency signals accurately using shared processing blocks instead of separate hardware for each frequency.

4. Why is calibration important in frequency-based communication systems?

During transmission, small frequency shifts can occur due to noise, hardware differences, or environmental factors. Calibration helps the receiver adjust to these shifts before decoding data. This ensures the system interprets frequency patterns correctly and reduces decoding errors, especially in narrowband and high-density communication systems.