A decade ago, memory systems behaved very differently from what we expect today. DRAM used to run at a fixed operating frequency once the system was powered on. Whether the device was streaming video, playing audio, or sitting nearly idle, the memory often continued running at the same speed.

This approach was inefficient. Running memory faster than necessary consumes extra power, generates unnecessary heat, and reduces battery efficiency, especially in portable devices.

US8407411B2 was designed to address this exact gap. The patent introduces a way for DRAM to observe its real workload and adjust its operating frequency accordingly, delivering performance when needed and saving power when it is not.

This energy-saving patent is also part of active litigation between Mingoe Consulting LLC and ASUSTeK Computer, Inc.

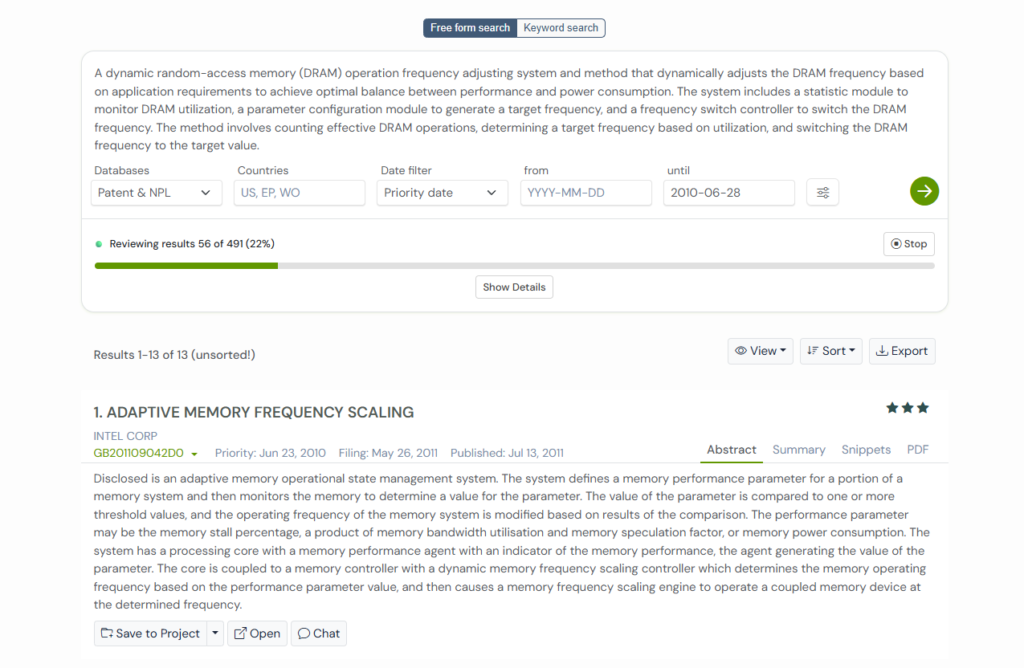

We wanted to find out how this idea evolved, so we put the Global Patent Search tool to work. The tool revealed where this invention sits within the broader evolution of smarter memory systems.

But first, let’s understand this patent a little more.

What Problem US8407411B2 Is Quietly Solving

To really understand this patent, it helps to picture what memory usually does behind the scenes.

Most DRAM systems follow a fixed routine. Once the system starts, the memory runs at a preset speed and sticks to it. It does not matter whether the system is decoding a high-definition video or just waiting for the next user input. The memory keeps spinning at the same pace.

US8407411B2, filed in 2010 by Wuxi Vimicro Corp., steps in right at this inefficiency. Instead of treating memory speed as a one-time decision, the invention treats it as something that should respond to real behavior. It watches how often the DRAM is actually doing useful work. Reading data, writing data, preparing rows. These actions are counted. Waiting around is not.

Over a short time window, the system builds a clear picture of how busy the memory really is. If the memory is mostly idle, running fast no longer makes sense. If it is constantly active, slowing down would hurt performance.

So the system adjusts. It lowers the frequency when work is light to save power. It raises the frequency when demand increases to keep things running smoothly. All of this happens automatically, without interrupting the system or losing data.

What looks like a small adjustment ends up making memory far more aware of the work it is actually doing.

Key Ideas That Make This System Work

At its core, this patent is built around a few practical ideas that help DRAM respond to real usage instead of running blindly.

- The system keeps track of when DRAM is actually working by counting real actions like reading and writing, not idle time.

- It calculates how busy the memory is over a short period instead of relying on assumptions made at startup.

- When memory usage is low, the system lowers the DRAM operating frequency to reduce power consumption.

- When memory usage becomes heavy, the system increases the frequency to maintain performance.

- Frequency changes are handled safely by temporarily switching DRAM into a self-refresh mode.

- Data requests are paused during frequency switching so no information is lost.

- Once the new frequency is set, DRAM resumes normal operation at the adjusted speed.

Together, these features allow memory to adapt smoothly as workloads change, balancing speed and power without manual tuning.

Not all performance optimization happens inside hardware components alone. Patent EP3107243B1 shows how device-level traffic awareness can dynamically manage network congestion by adjusting resource usage based on real-time activity states.

Looking at the Ideas That Came Before It

Long before US8407411B2 was proposed, engineers were already experimenting with ways to make memory behave more efficiently under changing workloads.

Some inventions tried to reduce unnecessary power draw, while others focused on keeping memory stable during timing changes. Together, these earlier designs form the foundation that made adaptive DRAM frequency control possible.

With the Global Patent Search tool, it becomes much easier to trace these connections and see how different approaches to memory management gradually evolved into more responsive systems like this one.

Let’s look at some of them.

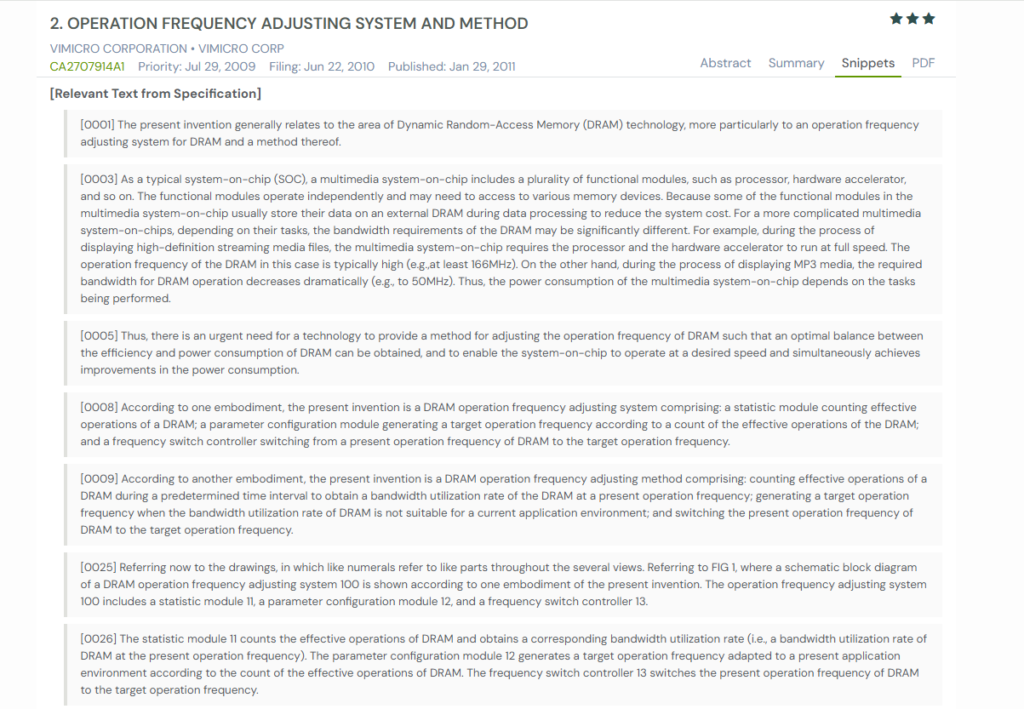

1. CA2707914A1

When multimedia chips started handling very different tasks back to back, memory systems struggled to keep up efficiently. A device might need high memory speed for video playback and much lower speed for audio or standby modes, yet DRAM often runs at a fixed frequency throughout.

CA2707914A1 addressed this mismatch by introducing a system that actively watches how DRAM is being used. Instead of assuming constant demand, it counts real memory actions like reads and writes over short time windows. From this, it figures out whether the memory is being underused or pushed too hard.

If usage is low, the system lowers the DRAM frequency to save power. If usage spikes, it increases the frequency to maintain performance. Like US8407411B2, it also switches frequencies safely by coordinating timing, refresh behavior, and control signals.

The Bigger Picture

This patent helps explain the early thinking behind adaptive DRAM frequency control and shows how measuring real workload became the foundation for smarter memory systems.

Power saving in memory systems is not limited to clock control alone. This becomes even clearer in Patent US7057960B1, which focuses on reducing energy use during memory refresh operations by selectively refreshing only active sections of memory.

2. US2008219083A1

Think about a checkout line at a store. Sometimes there’s a long queue. Sometimes there’s barely anyone waiting. If the cashier works at full speed all the time, even when no one is in line, that energy is wasted.

US2008219083A1, filed in 2008 by AFA technologies, looks at memory in the same way. Instead of guessing how busy memory is, it watches a buffer. The buffer is just a waiting area where data sits briefly before being written to memory or sent out after being read.

If this buffer keeps filling up, it means memory is not keeping up and needs to go faster. If the buffer stays mostly empty, it means memory is faster than necessary and can slow down.

This overlaps with US8407411B2 in intent. Both patents change memory speed based on what is actually happening in real time. The difference is how they measure activity. US8407411B2 counts memory operations. This patent watches how full the buffer gets.

The Bigger Picture

In the bigger picture, this patent shows an early and very intuitive way of making memory save power by slowing down when demand drops, instead of running at full speed all the time.

3. KR20070035349A

In many systems, multiple memory chips share the same clock. That means they all run fast or all slow down together, even if only one of them is actually being used. When some memory chips are idle but still running fast, power is wasted. When everything is slowed down together, performance can suffer.

KR20070035349A, filed in 2005, takes a more careful approach. Instead of treating all memory the same, it watches whether each memory channel is actually being accessed. If a channel is not used for a certain period, its clock frequency is lowered. If access starts again, the frequency is raised immediately.

This overlaps with US8407411B2 in a key way. Both patents change memory speed based on real activity, not fixed settings. US8407411B2 looks at how busy DRAM is overall, while this patent looks at access activity per memory channel. In both cases, speed follows usage.

The Bigger Picture

In the bigger picture, this invention shows an early move toward more selective memory control. It highlights how memory systems began saving power by slowing down only the parts that were idle, instead of slowing everything down or running everything at full speed all the time.

Not all efficiency gains come from hardware or clock control alone. Patent US9584633B2 shows how simplifying data flow and address management at the network layer can reduce delays and improve performance in high-traffic communication systems.

4. US2001011356A1

Early graphics chips faced a constant tradeoff. To keep video playback and live displays smooth, memory clocks were often set to run at full speed all the time. That worked for performance, but it drained the battery quickly, especially in portable devices where graphics activity came and went.

US2001011356A1, filed 1998 by ATI Technologies, approaches the problem by paying attention to who is asking for memory and how important that request is. The system watches different engines, like video capture, display, or 2D and 3D graphics, and checks whether they are actively using memory. High-priority tasks, such as real-time video, keep the memory clock running fast. Lower-priority tasks allow the clock to slow down when possible.

This overlaps with US8407411B2 in how decisions are made. Both patents adjust memory speed based on real activity instead of fixed settings. US8407411B2 looks at how busy DRAM is overall, while this patent looks at which engine is accessing memory and how critical that access is. In both cases, memory speed follows actual demand.

The Bigger Picture

In the bigger picture, this invention shows one of the earliest moves toward intelligent, activity-aware memory control. It highlights how memory systems began balancing performance and power by reacting to workload behavior rather than running at maximum speed all the time.

5. US7548481B1

As memory became faster, it also became one of the biggest power consumers in modern systems. Even when performance demands dropped, memory often kept running at high voltage and high speed, quietly burning energy. Lowering clock speed alone helped a little, but not enough to make a real difference.

Filed in 2006 by Nvidia Corp., US7548481B1 patent takes a stronger approach. Instead of adjusting only memory speed, it adjusts both speed and voltage together. When the system decides that full performance is not needed, it slows down the memory clock and also lowers the voltage supplied to the memory. Because voltage has a much bigger impact on power use than clock speed alone, this leads to far greater energy savings.

This overlaps with US8407411B2 in how decisions are triggered. Both patents adjust memory behavior dynamically rather than relying on fixed settings. US8407411B2 focuses on changing DRAM frequency based on workload, while this patent goes a step further by pairing frequency changes with voltage changes. In both cases, memory adapts to real operating conditions.

The Bigger Picture

In the bigger picture, this invention shows how memory power management evolved beyond simple clock control. It highlights a shift toward coordinated control of speed, voltage, and timing to reduce power without sacrificing system stability or performance.

How These Memory Ideas Compare Side by Side

Each of these patents tries to solve the same core problem: memory should not run fast all the time if the workload does not demand it. What differs is how each system measures activity and what it adjusts in response.

Looking at them together makes it easier to see how memory control gradually evolved toward the approach used in US8407411B2.

| Patent Number | Core Idea | How Activity Is Measured | What Gets Adjusted | How It Relates to US8407411B2 |

| CA2707914A1 | Adjust DRAM speed based on real usage | Counts non-idle DRAM operations over time | DRAM operating frequency | Very close overlap. Both monitor actual DRAM activity and change frequency dynamically |

| US2008219083A1 | Use buffer behavior as a workload signal | Watches how full or empty a buffer becomes | Memory clock frequency | Similar intent, different signal. Uses buffer fill instead of counting DRAM operations |

| KR20070035349A | Control memory per channel instead of all at once | Detects access activity on each memory channel | Clock frequency per SDRAM channel | Shares activity-based control, but applies it selectively per channel |

| US2001011356A1 | Prioritize memory speed based on task importance | Tracks which engine is requesting memory and its priority | Memory clock frequency | Uses workload priority rather than overall DRAM utilization |

| US7548481B1 | Reduce power more aggressively | System-level workload decision | Memory frequency and supply voltage | Extends the idea further by combining frequency scaling with voltage scaling |

Using GPS to Explore Memory Control Patents

Understanding a patent like US8407411B2 is not just about reading one document. The real insight comes from seeing how similar ideas appeared earlier, how they evolved, and where the overlaps or differences lie.

That kind of context is difficult to build by hand, especially when memory control techniques are spread across different companies, countries, and years. This is where the Global Patent Search platform becomes especially useful.

How to research this space using GPS:

- Start by entering the subject patent number, such as US8407411B2, into the GPS search bar.

- Review the related patents surfaced by GPS that share similar goals, such as frequency control, workload monitoring, or power reduction.

- Open the smart snippets to quickly understand how each patent measures activity, what it adjusts, and why it exists.

- Check structural patterns across patents, like operation counting, buffer monitoring, channel-based control, or voltage scaling.

- Dive deeper into full documents only when a concept shows meaningful overlap or differentiation.

By following this approach, GPS helps turn a long list of documents into a clear narrative of how memory systems became more adaptive over time. It reduces guesswork, saves research hours, and makes it easier to understand both technical direction and prior art risk.

If you want a faster, clearer way to analyze related patents and uncover meaningful connections, try the Global Patent Search tool today.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why does memory consume so much power even when activity is low?

In many systems, memory operates at a fixed clock speed and voltage that are set for peak performance. Even when data access drops, the memory continues running at this high setting. Because both clock activity and voltage remain unchanged, power is consumed continuously, leading to unnecessary energy use during idle or low-demand periods.

2. What does dynamic memory frequency control actually do?

Dynamic memory frequency control adjusts how fast memory operates based on real-time workload. When the system detects low activity, it reduces the memory clock to save power. When demand increases, the clock speed rises to maintain performance. This allows memory to match its energy use to actual system needs.

3. How does a system know when memory should speed up or slow down?

The system observes internal signals that reflect memory demand, such as read and write frequency, buffer occupancy, access timing, or which components are requesting data. By tracking these indicators over short intervals, the system can determine whether memory is underused or overloaded and adjust its operating speed accordingly.

4. Why is lowering voltage more effective than lowering clock speed alone?

Memory power consumption is strongly tied to voltage, often increasing with the square of the voltage level. As a result, reducing voltage produces a much larger power savings than reducing clock speed alone. In practice, systems often lower both voltage and frequency together to maximize energy efficiency without sacrificing stability.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice. The related patent references mentioned are preliminary results from the Global Patent Search tool and do not guarantee legal significance. For a comprehensive related patent analysis, we recommend conducting a detailed search using GPS or consulting a patent attorney.